Document 11275818

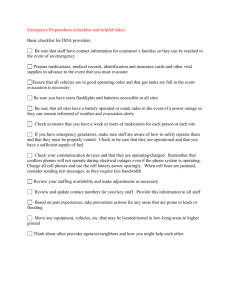

advertisement