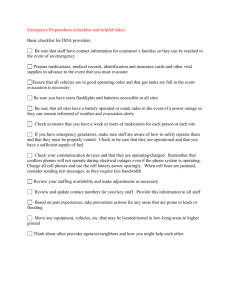

GAO NATIONAL PREPAREDNESS FEMA Has Made

advertisement