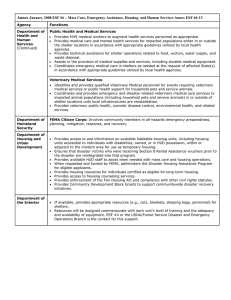

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS Opportunities Exist to Strengthen

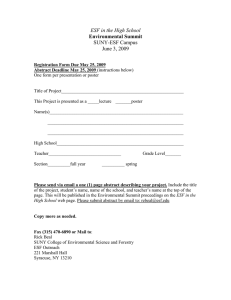

advertisement