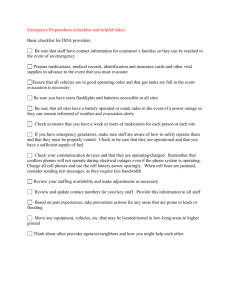

GAO EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS NRC Needs to Better

advertisement