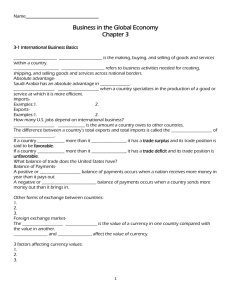

GAO COUNTERFEIT U.S. CURRENCY ABROAD Issues and U.S.

advertisement