GAO MARITIME SECURITY Varied Actions Taken to Enhance Cruise

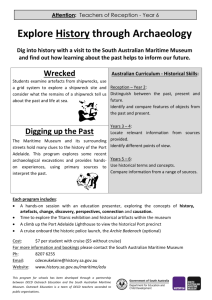

advertisement