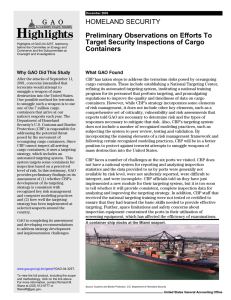

GAO SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY CBP Needs to

advertisement