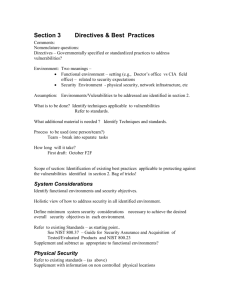

GAO INFORMATION SECURITY Better Implementation

advertisement