GAO FIREARMS TRAFFICKING U.S. Efforts to Combat

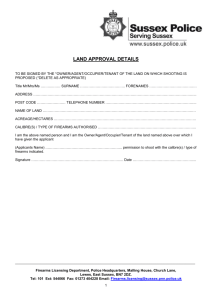

advertisement