GAO TERRORIST WATCH LIST SCREENING Opportunities Exist to

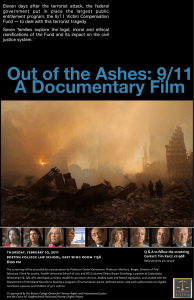

advertisement