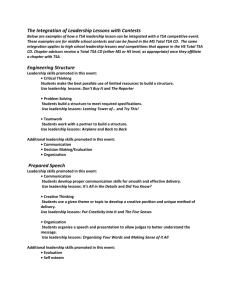

a GAO TRANSPORTATION SECURITY

advertisement