GAO HOMELAND SECURITY Much Is Being Done to

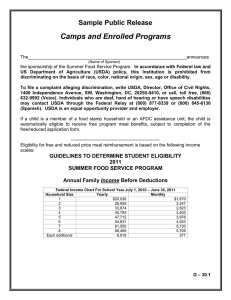

advertisement