GAO OVERSIGHT OF FOOD SAFETY ACTIVITIES

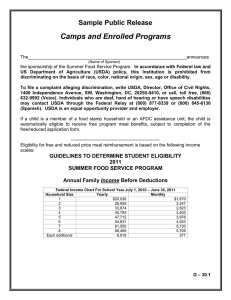

advertisement