GAO SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY CBP Works with

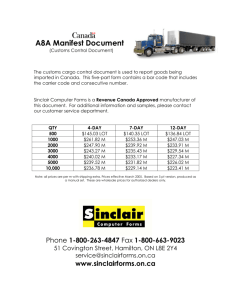

advertisement