Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies,

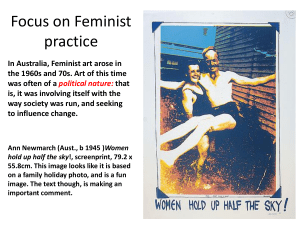

advertisement