GAO HOMELAND SECURITY INS Cannot Locate

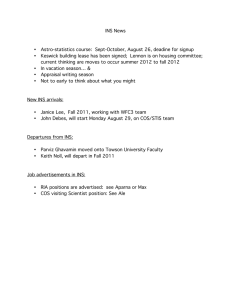

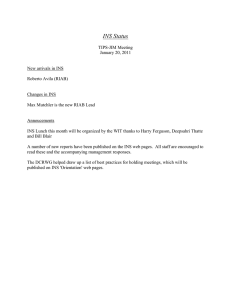

advertisement