GAO IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT Better Data and

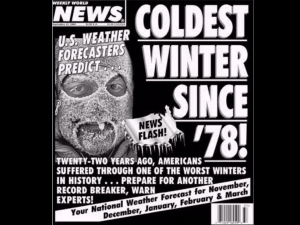

advertisement