GAO ALIEN DETENTION STANDARDS Telephone Access

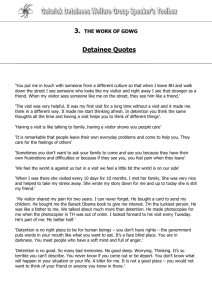

advertisement