GAO HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Visitor and

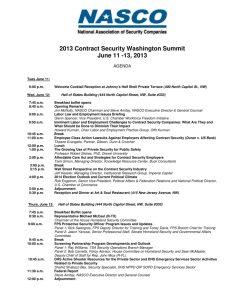

advertisement