GAO STATE DEPARTMENT Comprehensive Strategy Needed to

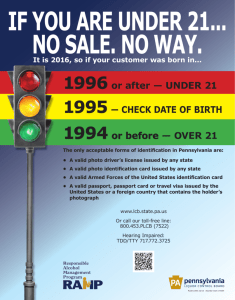

advertisement