GAO BORDER SECURITY Improvements in the Department of State’s

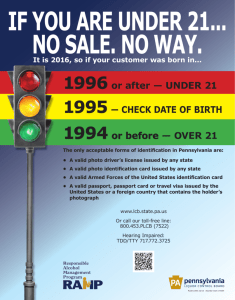

advertisement