GAO SOUTHWEST BORDER SECURITY Data Are Limited and

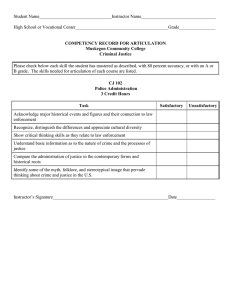

advertisement