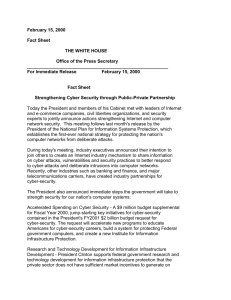

CRS Report for Congress Critical Infrastructures: Background, Policy, and Implementation

advertisement