CRIME, VIOLENCE, AND THE CRISIS IN GUATEMALA: OF THE STATE

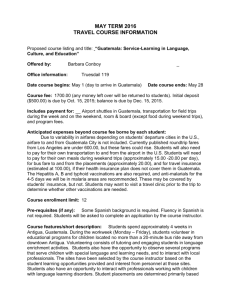

advertisement