Development of Infants with Disabilities and Their Families: Implications for... Service Delivery

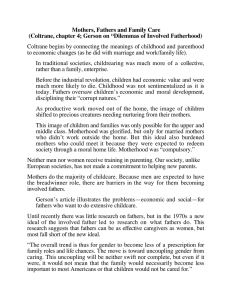

advertisement