Irrational Market:

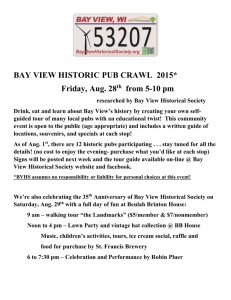

advertisement