Early Transfers of Contaminated Military Property

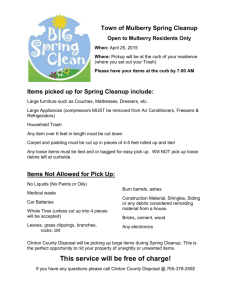

advertisement