STATE RENTAL PRODUCTION PROGRAMS by John Quinn

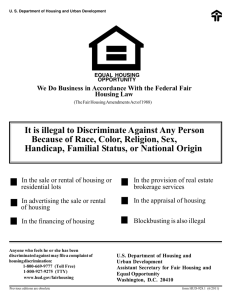

advertisement