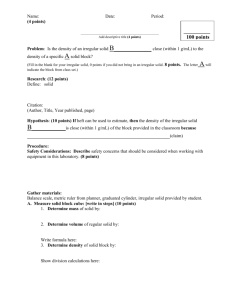

OCT 3

advertisement