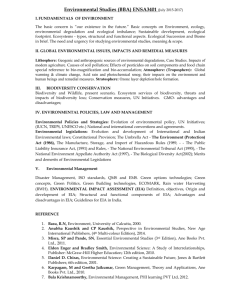

Environmental Impact Assessments in South Africa:

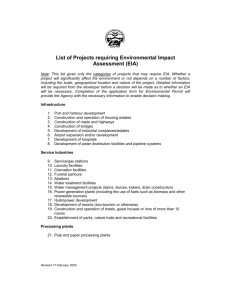

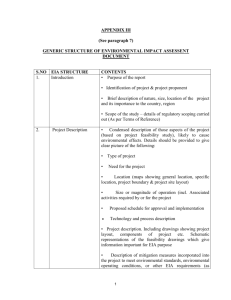

advertisement