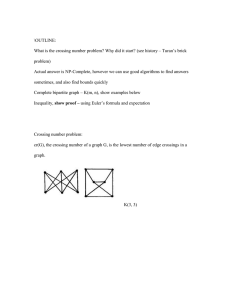

Reintegrating Living and Working Spaces: A

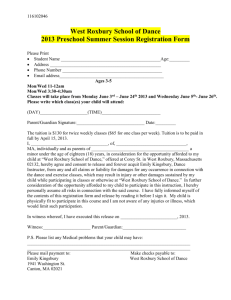

advertisement