Comments on DRAFT Groundwater Remedy Completion Strategy

advertisement

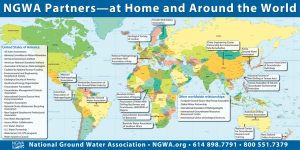

Comments on DRAFT Groundwater Remedy Completion Strategy The National Ground Water Association (NGWA) reached out to some of its members for feedback on U.S. EPA’s recent draft Groundwater Remedy Completion Strategy: Moving Forward with Completion in Mind. With their permission, the association is passing along the following two very thoughtful comments. The comments highlight the increased technical knowledge and expanded tool box that are now available while identifying other factors that may merit consideration as the nation seeks to address existing contaminated groundwater sites and determine a completion strategy. NGWA is neither endorsing nor promoting any position, but provides the following perspectives from practicing professionals in the field: The Tool Box Has Improved and Should Be Brought to Bear: Associates and I have reviewed in detail the USEPA draft document entitled “Groundwater Remedy and Completion Strategy: Moving Forward with Completion in Mind”. Basically we find the document to be a sensible, straight forward guidance in implementing, monitoring, evaluating, and amending/optimizing remediation systems. However I think two points are worthy of bringing to the attention of the authors: 1) Historically at most EPA Superfund groundwater remediation programs the remedy selected in the Record of Decision (ROD) entails the implementation of a single remediation technology (e.g. pump and treat through activated carbon). Under the subject EPA draft document process, this single technology would be implemented for a period then evaluated against performance metrics. If the remediation project utilizing this technology is shown to not be making adequate progress against Remedial Action Objectives (RAOs) and Clean Up Levels, a Management Decision would then be made as to whether or not to amend the project with other Remedial Alternatives. This is very reasonable. However, it would serve to streamline the Groundwater Remediation Completion Strategy if a planned use of combined technologies could be considered as the original remedy selected for the Record of Decision. We know now (unlike 30 years ago) that one technology will not reach RAOs and Clean Up Levels at most sites. This should be planned for up-front in the ROD with metrics in place to indicate when to switch from one technology to another (e.g. a groundwater Remedy written in the ROD that includes dual phase extraction then transition to in situ chemical oxidation then transition to monitored natural attenuation). 2) A significant concern arising from the Draft document as written is that there is no defined requirement for evaluating new or emerging technologies in the Focused Feasibility Study stage prior to moving the project from active to passive (institutional controls) or to petitioning for an ARAR waiver consistent with technical impracticability guidance (TI Waiver). Page 1 Undoubtedly, many potentially responsible parties will push for a movement directly toward a TI Waiver as their “exit strategy” from groundwater treatment and its associated costs, without evaluating the potential for new or emerging technologies to achieve RAOs and Clean Up Levels. “Back diffusion” has been shown to be a significant factor generating long-term low levels of contamination impacting groundwater at sites that have undergone a Remedy. This has spurred new research efforts by the scientific and engineering communities to develop better assessment tools and treatment technologies targeting back diffusion. Such technologies may enable successful treatment of many sites to RAOs and Clean Up Levels that otherwise would remain contaminated. The EPA should ensure that these new and emerging technologies are duly considered and properly evaluated on a site specific basis prior to considering a petition for TI Waiver. Other Factors to Consider in Determining a Completion Strategy This document does not address the broader issue of initially developing cleanup levels/remedial goals that may be more “practical” and take into account the likelihood of exposures to contaminants, and the use of institutional controls, such as deed restrictions, which are commonly used in many state programs to protect human health and the environment from contaminant concentrations that are not considered acceptable for “unrestricted use” (e.g., drinking of groundwater, residential or agricultural use of land/soil). In either instance, whether after a cleanup “failure” as discussed in Section 7.2 of the EPA document, or during the initial development of the remedial program, key issues that need to be considered when selecting/ developing the remedial alternative for a site are: Cost benefit analysis: are considerable funds being expended on an environmental exposure (or potential exposure) that can be relatively easily/less costly addressed in another manner (e.g., extension of a public water supply instead of costly, long-term, and uncertain source area and groundwater cleanup such as may occur with DNAPL in fractured bedrock); A realistic assessment of risks, including a realistic perspective on less likely risks (e.g., potential for groundwater to impact surface water quality); Application of institutional controls, including deed restrictions, to limit potential human and environmental exposures, in instances where these do not engender significant risk and are consistent with common practice outside the realm of CERCLA (e.g., capping of landfills and restriction of land use at/near landfill); Careful and consistent application of the Technical Impracticable waiver, which is a subjective assessment in many instances – realizing that disproportionate costs are inherently a part of the Page 2 calculus for assessment of TI, as well as technical/hydrogeologic issues and potential/actual risk implications; Cost should play a significant role in assessing TI, but in some instances, there may be more tolerance for higher costs than in others, such as when considering impacts to a sole source aquifer/water supply; Care should be taken to ensure that TI is not “overused” as a means to avoid remediation, but rather is a consideration that helps guide “smarter” (i.e., cost effective, likely to succeed) remediation. Background on the National Ground Water Association: The National Ground Water Association is a not-for-profit professional society and trade association for the groundwater industry. Our members from all 50 states include some of the country’s leading public and private sector groundwater scientists, engineers, water well contractors, manufacturers, and suppliers of groundwater-related products and services. The Association’s vision is to be the leading groundwater association that advocates the responsible development, management, and use of water For Information on this submission, contact: Christine Reimer National Ground Water Association 601 Dempsey Rd Westerville, OH 43081 800.551.7379, ext. 560 creimer@ngwa.org Page 3