An Alternative Planning Process for Improving

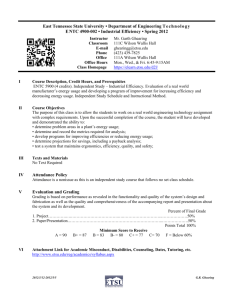

advertisement