Document 11259608

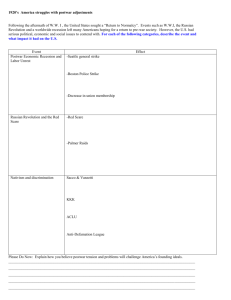

advertisement