working paper department economics technology

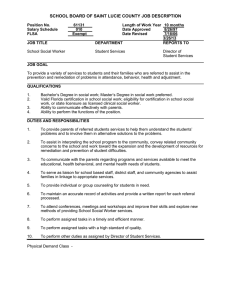

advertisement