Raptor Predation on Wintering Dunlins in Relation to the Tidal... Author(s): Dick Dekker and Ron Ydenberg

advertisement

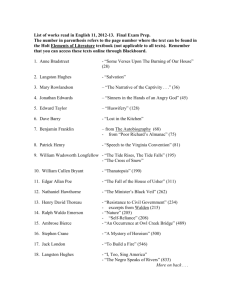

Raptor Predation on Wintering Dunlins in Relation to the Tidal Cycle Author(s): Dick Dekker and Ron Ydenberg Source: The Condor, Vol. 106, No. 2 (May, 2004), pp. 415-419 Published by: Cooper Ornithological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1370651 Accessed: 19-05-2015 18:31 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1370651?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Cooper Ornithological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Condor. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions SHORTCOMMUNICATIONS 415 1999. Temporal and geographic variaABOOKIRE. tion in fish communities of lower Cook Inlet, Alaska. Fishery Bulletin 97:962-977. Hobart,Tasmania. 2000. Benthic and peTREMBLAY, Y., ANDY. CHEREL. lagic dives: a new foraging behaviourin RockhopperPenguins.MarineEcology ProgressSeries 204:257-267. 8.1. SAS InstituteInc., Cary, NC. I. 1995. Marineecological processes.SpringSEALY, S. G. 1973. Adaptive significance of post- VALIELA, er, New York. hatchingdevelopmentalpatternsand growthrates in the Alcidae. Ornis Scandinavica4:113-121. ZAR, J. H. 1999. Biostatisticalanalysis. Simon and LTD.2000. Echoview v. 2.1. SONARDATAPROPRIETARY Schuster,UpperSaddle River,NJ. SAS INSTITUTE. 2000. SAS/STAT user's guide, version The Condor 106:415-419 ? The Cooper Ornithological Society 2004 RAPTOR PREDATION ON WINTERING DUNLINS IN RELATION TO THE TIDAL CYCLE DICK DEKKER1,3AND RON YDENBERG2 13819-112 A Street, Edmonton, AB T6J 1K4, Canada 2Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada Abstract. At Boundary Bay, British Columbia, 94 ejemplaresde Calidris alpina en 652 horas. Los Canada, Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) cap- dos m6todosprincipalesde caza fueronataquesabiertured 94 Dunlins (Calidris alpina) in 652 hunts. The tos sobreindividuosque estabanvolando (62%)y atatwo mainhuntingmethodswere open attackson flying ques encubiertossobreindividuosque estabanposados Dunlins (62%) and stealthattackson roostingor for- o forrajeando(35%).F. peregrinuscaz6 a lo largo del aging Dunlins (35%). Peregrineshunted throughout dia, pero la tasa de matanzapor hora de observaci6n the day, yet the kill rateper observationhourdropped disminuy6 1-2 hr antes de la pleamary alcanz6 un 1-2 hr before high tide and peaked 1-2 hr after high maximo 1-2 hr despu6sde la pleamar.La caida en la tide. The dropin kill ratecoincidedwith the departure tasa de matanzacoincidi6 con la partidaen masa de of the mass of Dunlins for over-oceanflights lasting C. alpina pararealizarvuelos sobreel oc6anoque du2-4 hr.The peak in kill rateoccurredjust afterthe tide raron 2-4 hr. El pico en la tasa de matanzaocurri6 began to ebb and the Dunlinsreturnedto foragein the justo despu6sde que la mareacomenz6 a menguary shore zone. The hypothesisthatcloseness to shoreline de que los individuosde C. alpina regresarona forravegetation is dangerousfor Dunlins is supportedby jear a la zona de playa.La hip6tesisde que la cercania three converginglines of evidence: (1) the high suc- de la vegetaci6na la linea de playa es peligrosapara cess rate (44%)of peregrinehuntsover the shorezone C. alpina es apoyadapor tres lineas convergentesde comparedto the rate (11%) over tide flats and ocean; evidencia:(1) la alta tasa de 6xito (44%) de las cace(2) the high kill rateper observationhourat high tide; rias de F. peregrinussobrela zona de playacomparada and (3) the positive correlationof kill rate with the con la tasa (11%) de las cacerias sobre los planos de heightof the tides. Seven of 13 Dunlinskilled by Mer- la mareay el oc6ano; (2) la alta tasa de matanzapor lins (Falco columbarius)and all five Dunlinskilled by hora de observaci6ndurantela pleamar;y (3) la corNorthernHarriers(Circuscyaneus)were also captured relaci6n positiva de la tasa de matanzacon la altura de las mareas. Siete de 13 individuos de C. alpina in the shore zone. cazados por F. columbariusy todos 5 individuosde words: Calidris Falco Key alpina,Dunlin, peregrinus, Peregrine Falcon, raptor predation, tidal cycle. Depredaci6n de Calidris alpina por Rapaces durante el Periodo Invernal con Relaci6n al Ciclo de la Marea Resumen. En la Bahia Boundary,Columbia Brit~nica, Canada,halcones Falco peregrinuscapturaron Manuscriptreceived29 May 2003; accepted12 November2003. 3E-mail:tj.dick-dekker@hotmail.com C. alpina cazados por Circus cyaneus tambi6n fueron atrapadosen la zona de playa. Predationrisk has been implicatedby many researchers as an importantdeterminantin the feedingbehavior of a wide variety of prey species (Lima et al. 1985, Milinski 1986). Accordingto theory, avian prey species balance predationrisk with foraging needs. For instance, in a trade-offbetween relative safety from predatorsand optimal caloric gain, forest passerines tend to forage close to the protectivecover of trees and bushes, whereas open-country birds stay well This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 416 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS away from vegetationthat could conceal raptors(Valone andLima 1987, Lima 1988). In estuarinehabitats, shorebirdsfrequentopen expanses of mudflatswhich allow for the timely discoveryof approachingraptors. Raptorsthathuntshorebirds,such as the PeregrineFalcon (Falco peregrinus) and the Merlin (Falco colum- barius), commonly use stealth methods to take their prey by surprise(Page and Whitacre 1975, Dekker 1980, 1988, Palmer1988, Cresswell 1996, Whiteet al. 2002). If rising tides inundatethe mudflatsand force the shorebirdsclose to the vegetated high-tide line, most leave andfly to roostingsites in adjacentcountry. In some locations,shorebirdsroost in habitatsthey do not normallyfrequent,such as agriculturallands(Butler 1994) or wave-sweptbeaches(Buchanan1996). On the northwest Pacific coast of North America, and probablyelsewhere in its extensive winteringrange, Dunlin flocks fly out over the ocean and remain in flightfor 2-4 hr until the tide turns.This behaviorwas strategyby Breninterpretedas a possible antipredator nan et al. (1985) and firstdocumentedas suchby Dekker (1998). Hotker(2000) saw the same phenomenon on the northcoast of Germanyandtermedit "airborne roosting."Stayingin flightover the waterfar offshore makes sense if roosting sites close to the high-tide markare dangerous.Ydenberget al. (2002) foundthat the choice of stopover sites by migrating Western Sandpipers(Calidrismauri)in BritishColumbia,Canada, could best be explained by a hypothesis that sandpipersare more vulnerableto raptorpredationon small feeding sites than on wide expanses of open mudflats. In this article, we examine a large data set of observed huntsand kills by PeregrineFalconsto test the hypothesis that proximity to shoreline vegetation is dangerousfor Dunlins,and thatDunlinstend to avoid risk when they are satiated,but are more willing to take risk when hungry.As additionalevidencefor that hypothesis,we also reporton Dunlin kills by Merlins (Falco columbarius) and Northern Harriers (Circus cyaneus). METHODS The study areawas at BoundaryBay, on the southern edge of the FraserRiver estuary(49005'N, 123000'W) in BritishColumbia,Canada.The bay is 16 km across and the intertidalzone is roughly 4 km wide at the lowest ebb. The tidal rhythmincludestwo flood tides, one usually higher than the other, per 24-hr period. During winter the highest tides almost always occur duringdaylighthours and inundateall intertidalmudflats and most of the narrowstripof saltmarsh,which is covered with low vegetation.A dyke protectslowlying agriculturalfields inland.BoundaryBay is a major stopoverfor migratorywaterbirdsand a wintering locationfor circa 50 000 Dunlinsand 1000 Black-bellied Plovers (Pluvialis squatarola). Birds of prey are common (Butler and Campbell 1987). In winter,the bay is huntedover by at least six peregrinesand one or more Merlins(Dekker2003). BetweenearlyNovemberandearlyFebruary,19942003, DD spentpartor all of 151 days (940 hr) in the study area, walking the dyke or sitting in a parked vehicle. Flocks of Dunlins were monitoredfor alarm behavior such as sudden flushing. Hunting raptors were also discoveredby frequentlyscanningthe area through8x wide-anglebinoculars.Perchedperegrines and Merlinswere often kept undersurveillancefor periods of up to 2 hr in the hope of seeing them hunt. We use the term "hunt"to mean a completedattack of which the outcome was known. A hunt could include one or more passes or swoops at the same Dunlin. An attackon a flock and subsequentpursuitof a single Dunlin fleeing that flock were counted as one hunt.However,if the falcon abandonedthe pursuitand again attackedthe same or a different flock, it was tallied as anotherhunt. This definitionof a hunt was also used by Dekker (1980, 1988, 2003) and is the equivalent of the term "attack" as formulatedby Cresswell (1996). In this paper,both terms are used interchangeably. Field data were recordedin diary form and entered into an annotatedtable of huntsand kills, dividedover three zones. Zone 1 representedthe saltmarshshore includinga 5-10 m stripof wrackand sparselyvegetated mud beyond the raggedmarshedge. To investigate whetherperegrinehuntingsuccess was influenced by distance from shore, we arbitrarilysplit the intertidal zone in two: zone 2 extended roughly 0.5 km from the saltmarsh;zone 3 lay beyond zone 2. Dependingon the tide height,zones 2 and 3 could consist of mudflatsand ocean. Although a hunt or pursuit might cross over from one zone into the next, the position of the prey at the startof the attackdefinedthe zone in which the hunt was consideredto have taken place. In a few borderlinecases, the choice amounted to a judgmentcall or best guess. Details on Peregrine Falcon characteristicsand huntingmethods,and Dunlin behaviorwhen avoidingraptorswere given in Dekker (2003). We recordedthe zone (1, 2, or 3) in which each hunt took place and the time until or since the nearest high tide. Fromthis summary,we derivedthe kill rate per observationhour in relation to the time of day (intervalsof 1 hr) and the time of the nearesthigh tide, based on the tide tablespublishedfor PointAtkinson, BritishColumbia.In a separatedataanalysis,RY compared the kill rate to the height of the tide (grouped into 40-cm intervals)at the time of the kill, using the algorithmavailableat XTide (Flater1998). The result was tested for significanceby standardregressionprocedures. The peregrinehunting success rate over the shore zone (zone 1) was compared statistically to zones 2 and 3 by a G-testof independence(Sokal and Rohlf 1981). No attemptwas madeto recordthe numberof Dunlins present in the attack zone when hunts and kills took place. Large numbersof Dunlins do not necessarily translateinto a high kill rate. On the contrary, singletons or small, isolated flocks of prey were reportedto be more vulnerableto stealthattacksby peregrines than large or multiple flocks spaced out over a wide area (Dekker 1980, 1998, Thiollay 1982). RESULTS A total of 652 peregrinehuntsdirectedat Dunlinswas observed. Of these, 94 ended in kills. Huntsand kills took place throughoutdaylighthours at averagerates This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions SHORTCOMMUNICATIONS 417 0.20a. TABLE 1. Success rates of PeregrineFalcons hunting Dunlinsat BoundaryBay, BritishColumbia,Canada. Zone 1 represents the ocean shore-saltmarsh edge; zone 2 extends 0.5 km beyond zone 1; zone 3 begins 0.5 km from the saltmarsh.Dependingon tide height, zones 2 and 3 could consist of mudflatsand ocean. 0.15 0.10 0.05 08:00 10:00 12:00 14:00 Zone 16:00 Time ofday c-b. 0.25 . Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Total 0.20 C) .0. 0- 0.10 00.05 -6 -5 4 -3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3 +4 +5 +6 ) from Hours hightide C C 0.20 0.15 0 0.10 , 0.05 2 3 4 5 Tideheight(m) FIGURE1. Temporaland tidal patternsof Peregrine Falcon predationon Dunlins wintering at Boundary Bay, BritishColumbia,Canada.(a) Kill rate (no. capturesper observationhr) in relationto the time of day. Numberof kills and observationtime (hr) in the successive intervalswere 1/49, 11/95, 15/117, 19/128, 13/ 136, 15/126, 13/127, 3/110, 4/52. (b) Kill raterelative to the crest of the nearesthigh tide. Numberof kills and observationtime (hr) in the successive intervals were 2/49, 3/55, 6/62, 5/75, 4/87, 12/100, 13/106, 25/ 104, 18/90, 3/79, 1/69, 2/58. (c) Correlation between kill rateandheightof the tide. The regressionequation is kill rate = 0.068 X tide height (m) - 0.16 (r2 = 0.86, F.5 = 29.8, P < 0.001). Number of kills and observationtime (hr) for the successivepoints were 0/ 25, 1/58, 8/104, 16/224, 26/279, 36/199, 7/50. No. hunts No. kills Success rate (%) 75 299 278 652 33 33 28 94 44 11 10 14 of 0.69 huntsper hr and 0.10 kills per hr.The kill rate per observationhour was quite consistentthroughout the day except for declines in early morning(08:0009:00) and late afternoon(15:00-16:00; Fig. la). The kill rate showed a strong associationwith the tidal cycle, rising with the flooding tide and falling with the ebbing tide (Fig. lb). The kill rate peaked 12 hr after high tide. The only anomalyin this pattern was a markedlow in kill rate beginning 2 hr before high tide. The rateduringthis 1-hrintervalwas nearly one-half of the previousintervaland one-thirdof the next. The kill rates also showed a strong and significant linear relationwith the height of the tide, rising steadily to 0.14-0.18 kills per hr at tide heights over 4.2 m (Fig. Ic). The success rate of hunts differedsubstantiallybetween zones and apparentlyas a function of the type of attack.In zone 1 all attackswere aimed at Dunlins roostingor feeding nearthe saltmarsh,and peregrines always attackedusing stealth, approachingvery low (<1 m) over the shoreline vegetation or rushing up over the dyke. Surprisecould be near complete, resultingin the captureof a Dunlinthe momentthe flock flushed in alarm.In zone 1, peregrineshad a success rateof 44% (33 kills in 75 hunts;Table 1). If a stealth huntin this zone was not immediatelysuccessful,peregrines rarelygave chase. The success rate of all hunts in zone 2 was nearly the same as in zone 3 (11% vs. 10%).Combined,the success rate of stealth hunts in these two zones was 14% (21 kills in 154 hunts), significantlylower than in zone 1 (G = 14.2, P < 0.001). Most (70%) hunts in zones 2 and 3 did not use stealth, but were open attackson Dunlinsin flightor of birdsthathad flushed well aheadof the falcon. These open attackson flying Dunlins had a success rate of 9% (37 kills in 406 hunts). The success rate of all peregrineattacksover zones 2 and 3 (11%) was significantlylower than all huntsover zone 1 (44%;G = 29.4, P < 0.001). Other raptorsalso attackedDunlins. Harriersfrequently attemptedto approachroosting Dunlins by stealth. Of an estimated300 harrierattacksonly five were successful and all of these took place in zone 1. Probably reflecting the low risk posed by harriers, Dunlins showed minimal avoidance response. If flushed by harriers,the Dunlins returnedto the same place as soon as the raptorhadpassedby. Merlinswere This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 418 SHORTCOMMUNICATIONS The peak in kill rate immediatelyafterhigh tide is probablydue to the Dunlins' need to compensatefor energy expendedduring2-4 hr of over-oceanflying. ReturningDunlinsare likely to be hungry,moreintent on foragingandless vigilantthanat othertimesduring the tidalcycle. Consequently,the trade-offtemporarily shifts towardincreasedrisk. A second and complementaryreason for the high kill rate just after high tide is that some peregrines, particularlythe adults,spendmost of the day perching and may not starthuntinguntil flocksof Dunlinsbegin to congregatenearthe saltmarsh.Adult peregrinesare DISCUSSION significantlymore successfulin the use of stealththan The hypothesis that raptor predationrisk for small juveniles. Only 25% of all hunts were by adults, yet shorebirdsincreases with closeness to vegetation is they accountedfor 47% of kills (Dekker2003). supportedin this study by three converging lines of PREYSELECTION evidence:(1) the high success rateof peregrineshunting over the saltmarshzone; (2) the relativelyhigh kill Based on the examinationof prey remains,a relatively rateper observationhourwhen Dunlinsare in the salt- high percentageof shorebirdscaught by raptorsare marshzone; and (3) the positive correlationof kill rate known to be juveniles (Kus et al. 1984, Whitfield with the height of the rising tide. The results of this 1985, Warnock1994). The mechanicsof age-related study also lend additionalsupportfor the hypothesis prey selectionseem simple if we assumethatjuveniles that the over-oceanflocking of Dunlins during high are on the outsides of flocks, either on the groundor wintertides is an antipredatorstrategy(Dekker 1998, in flight (Ydenbergand Prins 1984, Ruiz et al. 1989, Hotker2000). Flying far from shore, at varying alti- Newton 1998). In this study,at least 69% of captured tudes dependingon weather conditions, the Dunlins Dunlins were taken by peregrinesdirectly from the are safe fromthe most dangeroustype of raptorattack: outside or tail end of flocks (Dekker 2003). Furthermore, the percentage of juveniles may be high in a stealthapproachconcealedbehindvegetation. The overall percentageof stealth hunts by pere- small,isolatedflocksthatrenderthemselvesvulnerable to stealthattacks the high tide. Such risky begrines in this study (35%) is nearly equivalentto the haviorincludes during (1) late departureon over-oceanflock36% reportedin 233 shorebirdhunts on the coast of Scotland(Cresswell1996). By contrast,the percentage ing flights;(2) persistencein roostingor foragingalong of stealthflights in 569 shorebirdhuntsrecordedat a the high-tideline; (3) early returnto shore afteroverocean flocking; and (4) a switch to inland roosts or large marshylake in Albertawas 77% (Dekker1988). sites. The proportionof juveniles in flocks in feeding The explanationfor these dissimilarvalues is that the habitatin these two areas was quite different.At the such high-risksituations,and theirphysical condition to that flock over the ocean, lake, reedy shorelinescreatedsuitablecover for stealth compared conspecifics an avenue for furtherremight present interesting hunts. Open attackson flying shorebirdswere uncommon at the lake except when droughthad caused the search. shallows to recede well away from shore (Dekker This was financedby DD. During 1991, 1999). By the same token, the high proportion the last studytravelprivatelywere year, expenses partiallyreimbursed of open hunts at BoundaryBay (62%) reflectedthe lack of opportunitiesfor surpriseover zones 2 and 3. by the Centre for Wildlife Ecology at Simon Fraser Once the Dunlinswere >10 m from the saltmarsh(the University, British Columbia. Accommodation in 2000-2003 was providedby D. Leach. Occasionalcoboundarybetween zones 1 and 2), the distancefrom observerswere I. D. Hancock,R. Swanston, shorehad no significantbearingon the huntingsuccess and P. Thomas. G.Dekker, Court did the G-tests. I. Gordon rateof peregrines(i.e., kill ratesfor zones 2 and3 were assistedwith the dataanalysisfor Figureic. R. Dekker nearlyequivalent). the graphs.RefereesJ. Buchananand R. ButWhile peregrinesevidently hunt and captureprey prepared ler made helpful comments on the first draft of this throughoutthe day, the fact thatthey killed much less paper. often just before and much more often just after high tide cannot be relatedto habitat.If that were so, the LITERATURECITED kill rate per observationhour 1-2 hr before and 1-2 hr afterhigh tide shouldbe the same, which is clearly BRENNAN, L. A., J. B. BUCHANAN, S. G. HERMAN, AND not the case. The most plausible reason for the obT. M. JOHNSON. 1985. Interhabitat movements of serveddifferenceis relatedto the behaviorof the DunwinteringDunlinsin westernWashington.Murrelins. Well before the cresting tide, often when the let 66:11-16. floodwatersare still >50 m from the saltmarsh,the BUCHANAN,J. 1996. A comparison of behavior and success rates of Merlins and PeregrineFalcons great majorityof Dunlins departon their over-ocean when hunting Dunlins in two coastal habitats. flights, while othersfly inlandespeciallyduringor afJournalof RaptorResearch30:93-98. ter heavy rain.The drop in kill rate duringthis period reflectsthe decreasedvulnerabilityof the birdsduring BUTLER,R. W. 1994. Distribution and abundance of Western Sandpipers,Dunlins, and Black-bellied over-oceanflights.(Thekill rateat inlandroostingsites Plovers in the FraserRiver estuary,p. 18-23. In outside the study areawas not recorded.) far less commonthanharriers,but more adepthunters of Dunlins;7 of 23 stealthattackson flocks roosting in zone 1 were successful (30%).Merlinsalso hunted over zones 2 and 3, using stealthas the initialstrategy in 28 attacks on flocks. After the stealth approach failed, six captureswere made by persistentpursuitof single Dunlinsthathad left the flock (21%). Attacks by Merlins and peregrinesalways caused Dunlin flocks to move to anotherlocation or to begin theirover-oceanflights,which generallystarted1-2 hr before the rising tide inundatedall mudflathabitat. This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions SHORTCOMMUNICATIONS 419 R. W. Butler and K. Vermeer[EDS.],The abundance and distributionof estuarinebirds in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Canadian Wildlife Service OccasionalPaperNo. 83, Ottawa, ON, Canada. MILINSKI,M. 1986. Constraintsplacedby predatorson feeding behaviour,p. 236-252. In T. L. Pitcher [ED.], The behaviour of teleost fishes. Croom Helm Ltd., London. NEWTON, I. 1998. Populationlimitationin birds. Aca1987. The birds BUTLER,R. W., ANDR. W. CAMPBELL. demic Press, San Diego, CA. of the FraserRiverdelta:populations,ecology and PAGE, 1975. Raptorpredation G., ANDD. E WHITACRE. internationalsignificance.CanadianWildlife Seron winteringshorebirds.Condor77:73-83. Occasional No. Cavice 65, Ottawa,ON, Paper PALMER, R. S. 1988. Handbookof North American nada. birds. Vol. 5. Diurnal raptors,part 2. Yale UniW. 1996. Surprise as a winter hunting CRESSWELL, versity Press, New Haven,CT. strategy in Sparrowhawks,Peregrines,and MerANDE A. RuIz, G. M., P. G. CONNORS, S. E. GRIFFIN, lins. Ibis 138:684-692. PITELKA. 1989. Structureof a wintering Dunlin D. 1980. Huntingsuccess rates,foraginghabDEKKER, population.Condor91:562-570. its, and prey selection of PeregrineFalcons migrating throughcentral Alberta.CanadianField- SOKAL,R. R., ANDE J. ROHLF.1981. Biometry. Freeman and Co., New York. Naturalist94:371-382. D. 1988. PeregrineFalcon and Merlin pre- THIOLLAY, J. M. 1982. Les ressourcesalimentairesfacDEKKER, dation on small shorebirdsand passerinesin Alteur limitantla reproductiond'une populationinberta.CanadianJournalof Zoology 66:925-928. sulaire de Faucun Pelerins (Falco peregrinus D. 1991. Prairiewater:wildlife at Beaverhills DEKKER, brookei).Alauda50:16-44. Lake, Alberta. University of Alberta Press, Ed- VALONE, T. J., AND S. L. LIMA. 1987. Carryingfood Canada. monton,AB, items to cover for consumption:the behaviorof D. 1998. Over-ocean flocking by Dunlins DEKKER, ten bird species feeding underthe risk of preda(Calidrisalpina) andthe effect of raptorpredation tion. Oecologia 71:286-294. at Boundary Bay, British Columbia. Canadian WARNOCK, N. D. 1994. Biotic and abiotic factors afField-Naturalist112:694-697. fecting the distributionand abundanceof a winD. DEKKER, 1999. Bolt fromthe blue-wild peregrines tering populationof Dunlin. Ph.D. dissertation, on the hunt. Hancock House Publishing,Surrey, Universityof California,Berkeley,CA. BC, Canada. D. 2003. PeregrineFalconpredationon Dun- WHITE, C. M., N. J. CLUM,T. J. CADE, AND W. G. DEKKER, HUNT.2002. Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus). lins and ducks and kleptoparasiticinterference from Bald Eagles winteringin British Columbia. In A. Poole and E Gill [EDS.],The birdsof North Journalof RaptorResearch37:91-97. America, No. 660. The Birds of North America, FLATER,D. [ONLINE]. 1998. Xtide: harmonictide clock Inc., Philadelphia,PA. and tide predictor.<http://www.flaterco.com/xti- WHITFIELD,D. P. 1985. Raptorpredationon wintering de/> (1 December2003). wadersin southeastScotland.Ibis 127:544-558. HOTKER,H. 2000. When do Dunlins spend high tide YDENBERG, R. C., R. W. BUTLER, D. B. LANK, C. G. in flight?Waterbirds23:482-485. GUGLIELMO, M. LEMON, AND N. WOLF. 2002. Kus, B. E., P. ASHMAN,G. W. PAGE, AND L. E. STENTrade-offs, condition dependence and stopover ZEL. 1984. Age-relatedmortalityin a wintering site selection by migratingsandpipers.Journalof populationof Dunlin. Auk 101:69-73. Avian Biology 33:47-55. LIMA,S. L. 1988. Vigilance and diet selection:a simR. C., ANDH. H. T. PRINS.1984. Why do ple example in the Dark-eyed Junco. Canadian YDENBERG, birds roost communally?,p. 123-239. In P. R. Journalof Zoology 66:593-596. Evans, J. D. Goss-Custard,and W. G. Hale [EDS.], LIMA,S. L., T. L. VALONE,ANDT. CARACO.1985. ForCoastal waders and wildfowl in winter. Camaging efficiency--predationrisk trade-off in the grey squirrel.Animal Behavior33:155-165. bridge UniversityPress, Cambridge,UK. This content downloaded from 142.58.26.133 on Tue, 19 May 2015 18:31:34 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions