Document 11252540

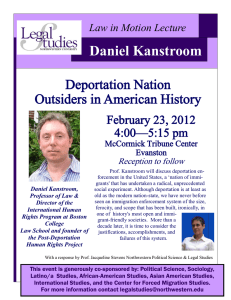

advertisement