An Engagement with God’s World: the Core Curriculum of Calvin College

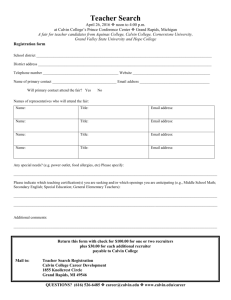

advertisement