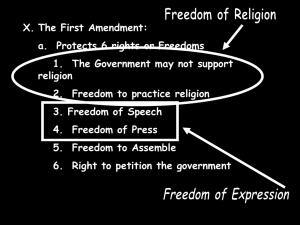

Symposium on Religion and Politics Religious Toleration in America

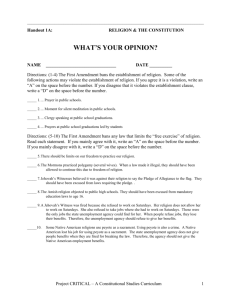

advertisement