The Cycling of Partitions and Compositions under Repeated Shifts Jerrold R. Griggs*

advertisement

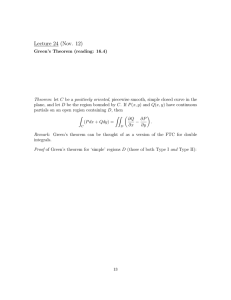

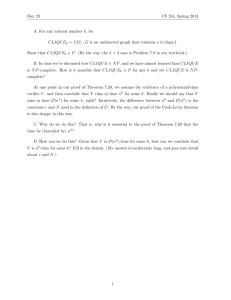

ADVANCES IN APPLIED MATHEMATICS ARTICLE NO. 21, 205]227 Ž1998. AM980597 The Cycling of Partitions and Compositions under Repeated Shifts Jerrold R. Griggs*, † and Chih-Chang Ho† Department of Mathematics, Uni¨ ersity of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina 29208 Received March 28, 1998; accepted May 5, 1998 In ‘‘Bulgarian Solitaire,’’ a player divides a deck of n cards into piles. Each move consists of taking a card from each pile to form a single new pile. One is concerned only with how many piles there are of each size. Starting from any division into piles, one always reaches some cycle of partitions of n. Brandt proved that for n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, the cycle is just the single partition into piles of distinct sizes 1, 2, . . . , k. Let D B Ž n. denote the maximum number of moves required to reach a cycle. Igusa and Etienne proved that D B Ž n. F k 2 y k whenever n F 1 q 2 q ??? qk, and equality holds when n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk. We present a simple new derivation of these facts. We improve the bound to D B Ž n. F k 2 y 2 k y 1, whenever n - 1 q 2 q ??? qk with k G 4. We present a lower bound for D B Ž n. that is likely to be the actual value. We introduce a new version of the game, Carolina Solitaire, in which the piles are kept in order, so we work with compositions rather than partitions. Many analogous results can be obtained. Q 1998 Academic Press 1. INTRODUCTION In the early 1980s, an article by Martin Gardner brought widespread attention to a card game that had attracted the curiosity of some European mathematicians. Called Bulgarian Solitaire, the game works as follows: First divide a finite deck of n cards into piles. A move consists of removing one card from each pile and forming a new pile. The operation is repeated over and over. We pay attention only to how many piles there are of each positive size, ignoring the locations of the piles. Thus, Bulgarian Solitaire can be viewed as a way of changing one partition into another. For instance, the partition into k parts of distinct * Research supported in part by NSA Grant MSP MDA904-95H1024. † Research supported in part by NSF Grant DMS-97-01211. 205 0196-8858r98 $25.00 Copyright Q 1998 by Academic Press All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. 206 GRIGGS AND HO sizes from 1 to k is preserved under the operation. Clearly, for any n, any start eventually leads to a cycle of partitions, since there are only finitely many partitions of n altogether. What is striking in playing the game is that, starting from any partition of a deck of size n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk cards, one always arrives eventually at this stable partition into sizes 1 through k. This effect is all the more dramatic in that it seems to take quite a while in some cases with only moderately large k, say k s 5. We do not know yet the reason for the appellation ‘‘Bulgarian.’’ However, we were introduced to an ordered variation of the game by a Bulgarian visitor, Andrey Andreev. In his game, which we shall call Carolina Solitaire, one also maintains an ordering of the nonempty piles. Say we begin with n cards divided into a row of piles of sizes c1 , . . . , c r ) 0, Ý i c i s n. One card is removed from each pile, and these r cards are then placed in a pile ahead of the others. Any exhausted pile Žsize 0. is ignored; only nonempty piles are considered. For a triangular number n, say n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, this game also appears to arrive at a stable division, with piles of sizes k, k y 1, . . . , 1. After proving this fact for Carolina Solitaire, as well as deriving bounds on how soon the cycling begins for arbitrary n, we asked experts for references to related work, and our search finally led us to the literature on Bulgarian Solitaire. Our methods are easily adapted to this simpler unordered game. In fact, we obtain improved bounds on the maximum number of shifts needed for any game on n cards to cycle. We shall also mention work on other variationŽs. of Bulgarian Solitaire, most notably one called Montreal Solitaire. Let us now define the games formally, present some examples and calculations, and describe the plan of the paper. For a positive integer n, we say l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . . is a partition of n, and we write l & n, provided the nonnegative integers l1 G l 2 G ??? add up to n. If l s ) l sq1 s 0, we say l has s parts, and we often drop the zeroes, writing l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s .. The shift operation B on l is the partition of n, denoted BŽ l., obtained by decreasing each part l i by one, inserting a part s, and discarding any zero parts. So B Ž i. Ž l. denotes the partition obtained by successively applying the shift operation B to l a total of i times. Starting with a partition l, we describe Bulgarian Solitaire by repeatedly applying the shift operation to obtain the sequence of partitions l , B Ž l . , B Ž2. Ž l . , . . . . For a couple of simple examples, we note that l s Ž2, 1, 1, 1, 1. & 6 gives the sequence Ž2, 1, 1, 1, 1., Ž5, 1., Ž4, 2., Ž3, 2, 1., Ž3, 2, 1., . . . , while l s Ž6, 1. & 7 yields Ž6, 1., Ž5, 2., Ž4, 2, 1., Ž3, 3, 1., Ž3, 2, 2., Ž3, 2, 1, 1., Ž4, 2, 1., . . . . The first example is fixed at the partition Ž3, 2, 1. after three steps, while the second example reaches a cycle after two steps. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 207 We say a partition m & n is B-cyclic if B Ž i. Ž m . s m for some i ) 0. Brandt w3x characterized all B-cyclic partitions for Bulgarian Solitaire. In particular, when n is a triangular number, 1 q 2 q ??? qk, he proved that Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 2, 1. is the unique B-cyclic partition of n, one that we end up with, no matter where we start. Note that if n is not triangular, there is no fixed partition under B. To measure how long it takes for Bulgarian Solitaire to cycle, for l & n we let d B Ž l. denote the smallest integer i G 0 such that B Ž i. Ž l. is B-cyclic. Let D B Ž n. [ max d B Ž l.: l & n4 , so that for any l & n, D B Ž n. steps reach a cycle. Trivially, D B Ž1. s D B Ž2. s 0 and D B Ž3. s 2. The values of D B Ž n., 4 F n F 36, are displayed in Fig. 1, which we worked out by computer. The data are arranged using the representation n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r F k. Brandt w3x conjectured that D B Ž n. s k 2 y k for triangular n, n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk. Hobby and Knuth w7x confirmed this for k F 10 by computer. It was first proven by Igusa w8x and Etienne w5x, apparently independently at about the same time, although Etienne’s proof was published much later. ŽNote that Etienne’s paper is noted as having been received in 1984.. In 1987 Bentz w2x also gave a different proof. In Section 2 we present our proof of Brandt’s result characterizing all B-cyclic partitions. This leads to our simple, new proof of the value of D B Ž n. for triangular numbers n, given in Section 3. Igusa and Etienne went on to obtain the upper bound D B Ž n. F k 2 y k for general n, represented as 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r F k. It is by no means sharp for every n Žsee Fig. 1.. Igusa w8x mentioned that this bound follows easily from Brandt’s conjecture using a comparison theorem by Akin and Davis w1, Theorem 3Žc.x. We will describe this comparison theorem and show the implication in Section 4. We then prove a better general bound ŽTheorem 4.4., which is D B Ž n. F k 2 y 2 k y 1, when 1 F r - k and k G 4. ŽCases n s 2, 5 violate the bound.. We also present a FIG. 1. D B Ž n. for n s 4, 5, . . . , 36. 208 GRIGGS AND HO lower bound for D B Ž n. that we suspect is the correct value in general, although a proof of this claim has eluded us. In Section 5 we consider Carolina Solitaire, the ordered version of Bulgarian Solitaire. Analogously with d B Ž l. and D B Ž n. for Bulgarian Solitaire, we introduce d C Ž l. and D C Ž n. for Carolina Solitaire. We show that, for triangular n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, D C Ž n. s k 2 y 1. For other n of the form n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r - k, we prove D C Ž n. F k 2 y k y 2, provided that k G 4. We also present a lower bound for D C Ž n. that we conjecture is the correct value in general. Other variations of Bulgarian Solitaire have been introduced: Yeh and Servedio w9, 10x studied a variation on circular compositions; Cannings and Haigh w4x investigated ‘‘Montreal Solitaire,’’ in which game the rule from l to BŽ l. is changed when an exhausted pile Žsize 0. in l occurs. Akin and Davis w1x also introduced ‘‘Austrian Solitaire.’’ In this game, a special pile called the bank is reserved. Each move consists of taking a card from each pile into the bank, and then generating some new piles from the bank by a certain rule. 2. CHARACTERIZING CYCLIC PARTITIONS We begin by describing B-cyclic partitions of n, a result discovered by Brandt w3x. Etienne w5x as well as Akin and Davis w1x also gave proofs. Although Etienne proved the result for triangular n only, the idea in his proof is simple and can be applied to general n. The approach presented here is similar to Etienne’s and we include it for the reader’s benefit. THEOREM 2.1 w3x. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r F k. Then l & n is B-cyclic if and only if l has the form Ž k y 1 q d ky 1 , k y 2 q d ky2 , . . . , 2 q d 2 , 1 q d 1 , d 0 . , 1 where each d i is 0 or 1 and Ý ky is0 d i s r. COROLLARY 2.2. If n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, then Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 2, 1. is the unique B-cyclic partition of n. In order to prove the theorem, we introduce a natural array representation of a partition l. We are particularly interested in how repeatedly shifting l affects the position of the ones in the array. For a partition l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . & n, we associate a Ž0, 1.-array ` Ml s w m i j x i , js1 , where m i j s ½ 1, if j F s and i F l j , 0, otherwise. The columns of Ml correspond to the parts of l. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 209 We notice that M B Ž l. can be obtained directly from Ml by a shifting process on a Ž0, 1.-array. In later sections, such a shifting process can help us evaluate d B Ž l. easily for some particular partitions l. We describe this shifting process as follows: For a Ž0, 1.-array M, we say that the wth diagonal of M consists of entries m i j , where i q j y 1 s w. Assume l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . & n and its associated array Ml is given. Step 1: Diagonally circular shifting. For each diagonal of Ml, say ¨ 1 , ¨ 2 , . . . , and ¨ w are the entries Žlisted from left to right. in this diagonal, we replace them by ¨ w , ¨ 1 , ¨ 2 , . . . , and ¨ wy1 , respectively. Then we obtain a new array; denote it MlX . Note that the numbers of ones in columns of MlX are s, l1 y 1, l 2 y 1, . . . , l s y 1, 0, 0, 0, . . . . If s G l1 y 1 then MlX is the array M B Ž l. . If s - l1 y 1 then we need an extra step to obtain M B Ž l. . Step 2: Left shifting. We remove all zero entries in the first column of MlX and shift each entry at the Ž i, j .-position, i G s q 1, j G 2, to the Ž i, j y 1.-position. The new array is M B Ž l. . Figure 2 shows two examples of the shifting process described above. Proof of Theorem 2.1. Ž¥. Assume that l has the stated form. The array Ml has all ones on the first k y 1 diagonals and all zeroes beyond diagonal k. Each shift just shifts entries on diagonal k. Thus, B Ž k . Ž l. s l, and l is B-cyclic. Ž«. In the shifting process, we notice that Step 1 keeps every entry on the same diagonal, while Step 2 always brings the entry 1 at the Ž s q 1, 2.-position to a diagonal with smaller index. Thus, for any B-cyclic partition m , the shifting process from Mm to M B Ž m . should involve Step 1 only. FIG. 2. A shifting process on the arrays. 210 GRIGGS AND HO Now assume that l is B-cyclic and l cannot be expressed in the stated form. Then for some w, there is a 0 in the wth diagonal and a 1 in the Ž w q 1.th diagonal. Since the series of shifting processes from Ml to M B Ž l . to M B Ž2. Ž l . , and so on involves Step 1 Ždiagonally circular shifting. only, and since the integers w and w q 1 are relatively prime, we will reach Žin at most w 2 y w y 1 steps. an array Mm which has 0 as Ž1, w .-entry and 1 as Ž w q 1, 1.-entry. ŽFigure 3 shows an example for such a series of shifting processes.. Then the shifting process from Mm to M B Ž m . involves Step 2, a contradiction. It is easy to see from Theorem 2.1 that for a given n with r s k, k y 1, or 1, starting from any partition of n and repeatedly applying the shift operation B always reaches a unique cycle of partition of n. FIG. 3. A series of shifting processes on the associated array of l s Ž2, 2, 1, 1.. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 211 For general n, Brandt w3x also showed that the number of cycles for Bulgarian Solitaire is 1 Ý k d <gcdŽ k , r . f Ž d. krd , rrd ž / where f Ž d . is the Euler f-function. The derivation of this formula was explained in detail later by Akin and Davis w1x. 3. EVALUATING D B Ž n. FOR TRIANGULAR NUMBERS n The partition l s Ž2, 2, 1, 1. in Fig. 3 gives D B Ž3. G 3 2 y 3. In general, we have THEOREM 3.1 w1, 2, 5x. If n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, then D B Ž n. G k 2 y k. Proof. It suffices to present l & n such that d B Ž l. s k 2 y k. Let l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l kq1 ., where l1 s k y 1, l i s k y i q 1 for i s 2, 3, . . . , k, and l kq 1 s 1. By repeatedly applying the shifting process Ždescribed in the previous section. to the arrays Ml, M B Ž l. , . . . , it is easy to see that B Ž k . Ž l . s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l ky1 , l k q 1 . , B Ž2 k . Ž l . s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l ky1 q 1, l k . , .. . B ŽŽ ky2. k . Ž l . s Ž l1 , l2 , l 3 q 1, l 4 , l5 , . . . , l k . , B ŽŽ ky1. ky1. Ž l . s Ž l1 q 2, l2 , l 3 , . . . , l ky1 . , B ŽŽ ky1. k . Ž l . s Ž k, k y 1, k y 2, . . . , 2, 1 . . Therefore d B Ž l. s k 2 y k. Before we prove in Theorem 3.7 that, for triangular n, the lower bound k 2 y k is the actual value of D B Ž n., we need some notation and lemmas. Let us start with the example for n s 15: The 176 partitions of 15 can be arranged in a tree illustrated in Fig. 4 Žfrom w3x. so that the vertices correspond to the partitions and going down corresponds to applying B. ŽThus, the root of the tree is the partition Ž5, 4, 3, 2, 1... In this figure, each vertex is labeled with the number of parts for its corresponding partition. For a partition l & n, we associate a sequence seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :, where c i is the number of parts in B Ž iy1. Ž l.. For instance, the top left vertex in Fig. 4 Žcorresponding to the partition l s Ž4, 4, 3, 2, 1, 1. & 15. 212 GRIGGS AND HO FIG. 4. A tree for the partitions of 15. has the associated sequence seq B Ž l. s ²6, 5, 5, 5, 4, 5, 6, 5, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 5, 4, 5, 5, 5, 6, 4, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, . . . :. In Fig. 4, we observe that the pattern ‘‘x y 1, x, x, . . . , x, x q 1’’ appears quite often in most associated sequences. It will play a pivotal role in our process for evaluating D B Ž n.. To study this pattern, we associate each partition with a diagram: Given a partition l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . & n, let seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . : be its associated sequence. Then diagram B Ž l. is defined to be the diagram shown in Fig. 5, where each l i-column Žresp., c i-column. has l i Žresp., c i . ones on the top and has infinitely many zeroes on all other entries. For example, if l s Ž4, 2, 2, 2. then diagram B Ž l. is shown in Fig. 6Ža.. We notice that there are c i ones in the row corresponding to c i . Furthermore, diagram B Ž l. can be regarded as bookkeeping for the shift CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 213 FIG. 5. diagram B Ž l.. operation B on l, since we can easily obtain B Ž i. Ž l. from diagram B Ž l. for any integer i. For example, the rectangle below c 3 Žsee Fig. 6Žb.. gives B Ž3. Ž l. s Ž4, 3, 2, 1. and the rectangle below c6 gives B Ž6. Ž l. s Ž4, 3, 2, 1.. PROPOSITION 3.2. Then Assume n G 1, l & n, and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. Ž1. c iq1 F c i q 1 for i G 1; Ž2. for n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, where 1 F r F k, the sum of any k consecuti¨ e terms in the sequence is at most k Ž k y 1. q r; FIG. 6. Ža. diagram B Ž l. for l s Ž4, 2, 2, 2.. Žb. The rectangle below c 3 . 214 GRIGGS AND HO Ž3. Ž the sandwich property . if i - j and c i - x - c j , then there exist integers p and q such that i F p - q F j, q G p q 2, and Ž c p , c pq1 , . . . , c q . s Ž x y 1, x, x, . . . , x, x q 1.. Proof. Ž1. follows from the definition of the shift operation B. To prove Ž2., we see for i ) 0 in diagram B Ž l. that c iq1 q c iq2 q ??? qc iqk is the number of 1s in the k rows labelled by c iq1 , c iq2 , . . . . These come from B Ž i. Ž l. Žin the rectangle below c i ., or from the staircase consisting of j y 1 squares to the right of c iqj , 1 F j F k. Thus, c iq1 q ??? qc iqk F n q 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. s k Ž k y 1. q r. For Ž3., choose p as large as possible such that i F p - j and c p F x y 1. We next require a series of lemmas that rely on Proposition 3.2 and diagram B Ž l.. LEMMA 3.3. Then Let l & n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. Ž1. d B Ž l. s t, where ² c t , c tq1 , . . . : s ² k y 1, k, k, . . . :; Ž2. if d B Ž l. s t G k q 1 then at least one of the following holds: Ži. Ž c p , c pq1 , . . . , c q . s Ž k y 1, k, k, . . . , k, k q 1. for some p, q with t y k F p - q F t y 1 and q G p q 2; Žii. Ž c p , c pq1 , . . . , c q . s Ž k y 2, k y 1, k y 1, . . . , k y 1, k . for some p, q with t y k q 1 F p - q F t q 1 and q G p q 2. Proof. Ž1. By Theorem 2.1, we have d B Ž l. s t where seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , . . . , c t , k, k, k, . . . : and c t / k. Then Proposition 3.2 forces c t s k y 1. Ž2. For i ) j, e i, j denote the entry in the c i-row and the c j-column of diagram B Ž l.. Then e t, ty1 s 1. Since c t s k y 1, we have e t, i s 0 for some i, t y k F i F t y 2. We choose such i as large as possible. Then e t, iq1 s 1, and, since c tq1 s k s c t q 1, comparing rows for c t and c tq1 in diagram B Ž l., we have e tq1, iq1 s 1 as well. The column below c iq1 then has ones down at least as far as the row for c tq1. Proposition 3.2Ž1. gives c i G c iq1 y 1, which forces all entries in the c i-column above the 0 at e t, i to be ones. Therefore, c i s t y i y 1 and c iq1 s t y i. If i G t y k q 1, then c i F k y 2, and Žii. holds by the sandwich property. Else, we have i s t y k, c tyk s k y 1, and c tykq1 s k. If c j F k y 2 for some j, t y k q 2 F j F t y 1, Žii. holds by the sandwich property, while if c j G k q 1 for some such j, Ži. holds. Else, suppose for contradiction that k y 1 F c j F k, for j s t y k q 2, t y k q 3, . . . , t y 1: Since i s t y k, the row for c t in diagram B Ž l. consists of k y 1 ones followed by all zeroes. The row for c tq1 is then k ones followed by all zeroes. There are k ones at the tops of columns c tq1 , c tq2 , . . . . Hence, in the rectangle CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 215 below c ty1 , we have just k y 1 ones in the first row, followed by k y j q 1 ones in row j, 2 F j F k. Rows below that are all zero. In total, we have n y 1 ones in the rectangle, which is a contradiction since this rectangle represents, after reordering the columns if necessary, a partition of n. LEMMA 3.4. Let l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . & n G 1 and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. If, for some p, k, Ž c p , . . . , c pqk . s Ž k y 2, k y 1, k y 1, . . . , k y 1, k . , then p q k F n q 1. Proof. Let e i, j Žresp., f i, j . denote the entry in the c i-row and the c j-column Žresp., l j-column. of diagram B Ž l.. Then we have e pqky2, p s 1 and e pq ky1, p s 0, since c p s k y 2. By the given condition, in the c pqk-row we also have e pq k, j s 1 for j s p q 1, p q 2, . . . , p q k y 1. Note that in addition to these k y 1 entries of 1, there is exactly one more 1 in the c pq k-row, since c pqk s k. If f pq k, j s 1 for some j, 1 F j F s, then p q k F l j F n. Else, e pqk, j s 1 for some j, 1 F j F p y 1. In fact, j s 1, for, otherwise, we have e pq k, jy1 s 0, and, since c pqk s k s c pqky1 q 1, comparing rows for c pqk and c pq ky1 in diagram B Ž l., we also have e pqky1, jy1 s 0. Similarly, since c pq ky1 s c pqky2 , e pqky2, p s 1, and e pqky1, p s 0, and comparing rows for c pq ky1 and c pqky2 in diagram B Ž l., we have e pqky2, jy1 s 0. Then c j ) c jy1 q 1, a contradiction. So j s 1, and then p q k y 1 F c1 F n. LEMMA 3.5. Let l & n G 1 and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. If for some integers x, p, q, q G p q 3, and Ž c p , c pq1 , . . . , c q . s Ž x y 1, x, x, . . . , x, x q 1 . , then either p F x or Ž c p9 , c pXq1 , . . . , c q9 . s Ž xX y 1, x9, xX , . . . , xX , xX q 1 . for some integers xX , pX , qX with xX F x, 2 F qX y pX - q y p, and p y x F pX - qX F p q 1. Proof. We assume p G x q 1 and prove the existence of xX , pX , and qX . For i ) j, let e i, j denote the entry in the c i-row and the c j-column of diagram B Ž l.. Then e p, py1 s 1. Since c p s x y 1, we have e p, p9 s 0 for some p9, p y x F p9 F p y 2. We choose such p9 as large as possible. Then e p, j s 1 for j s pX q 1, pX q 2, . . . , p y 1, and, since c pq1 s x s c p q 1, comparing rows for c pq 1 and c p in diagram B Ž l., we also have e pq 1, j s 1 for j s pX q 1, pX q 2, . . . , p. The column below c p9q1 then has ones down at least as far as the row at c pq 1. Proposition 3.2Ž1. gives c p9 G c p9q1 y 1, which forces all entries above the zero at e p, p9 to be ones. Therefore c p9 s p y p9 y 1, c p9q1 s p y p9, and e pq2, p9q1 s 0. 216 GRIGGS AND HO Since c pq 2 s x s c pq1 , comparing rows for c pq2 and c pq1 in diagram B Ž l., we have e pq2, j s 1 for j s p9 q 2, p9 q 3, . . . , p q 1. If e pq 3, p9q2 s 1 then c p9q2 s p y p9 q 1, and we are finished. So we may assume e pq 3, p9q2 s 0 and c p9q2 s p y p9. Since c pq 3 s x s c pq2 , comparing rows for c pq3 and c pq2 in diagram B Ž l., we have e pq3, j s 1 for j s p9 q 3, p9 q 4, . . . , p q 2. If e pq 4, p9q3 s 1 then c p9q3 s p y p9 q 1, and we are finished. So we may assume e pq 4, p9q3 s 0 and c p9q3 s p y p9. Continue this process. So we may assume e qy 1, p9qqypy2 s 0, c p9qqypy2 s p y p9, and e qy1, j s 1 for j s p9 q q y p y 1, p9 q q y p, . . . , q y 2. Since c q s x q 1 s c qy 1 q 1, comparing rows for c q and c qy1 in diagram B Ž l., we have e q, p9qqypy1 s 1, and hence c p9qqypy1 s p y p9 q 1. This completes the proof. LEMMA 3.6. Let l & n G 1 and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. If Ž c p , c pq1 , c pq2 . s Ž x y 1, x, x q 1 . , then p F x. Proof. For i ) j, let e i, j denote the entry in the c i-row and the c j-column of diagram B Ž l.. Then e p, py1 s 1. Assume the contrary, i.e., p ) x. Then c p s x y 1 - p y 1 implies e p, i s 0 for some i, 1 F i F p y 2. Choose such i as large as possible. Then e p, iq1 s 1. Since c pq1 s x s c p q 1 and c pq2 s x q 1 s c pq1 q 1, comparing rows for c p , c pq1 , and c pq 2 in diagram B Ž l., we also have e pq2, iq1 s e pq1, iq1 s 1. Thus c iq1 ) c i q 1, a contradiction. We are now in a position to prove THEOREM 3.7 w5, 8x. If n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, then D B Ž n . s k 2 y k. Proof. Note that from Theorem 3.1 we have D B Ž n. G k 2 y k. Now we prove D B Ž n. F k 2 y k. Let l & n. It suffices to show d B Ž l. F k 2 y k. We may assume k G 3, since it is easy to verify that d B Ž l. F k 2 y k for k s 1, 2. Further, we may also assume d B Ž l. G k q 1. ŽOtherwise, d B Ž l. F k - k 2 y k, since k G 3.. Let seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :, where ² c t , c tq1 , . . . : s ² k y 1, k, k, k, . . . :. Then d B Ž l. s t and at least one of Ži., Žii. of Lemma 3.3 holds. If Žii. holds with q s p q k, we have p s t y k q 1 and q s t q 1. Note that Lemma 3.4 gives p q k F n q 1. Then d B Ž l. s t s p q k y 1 F n F k 2 y k, since k G 3. Else, Ži. or Žii. holds and q F p q k y 1. By Lemmas 3.5 and 3.6, seq B Ž l. has at most k 2 y 2 k y 1 terms before the c p-term. Then d B Ž l. s t F Ž p y 1. q k q 1 F Ž k 2 y 2 k y 1. q k q 1 F k 2 y k. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 217 We observe that, for k s 2 Žresp., k s 3., l s Ž1, 1, 1. Žresp., l s Ž2, 2, 1, 1.. is the only partition of n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk achieving d B Ž l. s k 2 y k. For k G 4, we have THEOREM 3.8. Let k G 4 and n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk. If l & n with d B Ž l. s k 2 y k, then the associated array Ml s w m i j x`i, js1 satisfies the following conditions Ž illustrated in Fig. 7.: Ž1. Ž2. Ž3. m i j s 1 for j F k q 3 y 2 i; m i j s 0 for j G 2 k q 1 y 2 i; <Ž i, j .: j s k q 4 y 2 i, m i j s 04< F 2. Proof. If k G 4 and d B Ž l. s k 2 y k, the proof of Theorem 3.7 implies Ži. of Lemma 3.3 holds and q s p q k y 1. Further, we have seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :, where Ž c k , c kq1 , c kq2 . s Ž k y 1, k, k q 1. and Ž c 2 k , c 2 kq1 , c 2 kq2 , c 2 kq3 . s Ž k y 1, k, k, k q 1.. For i ) j, let e i, j denote the entry in the c i-row and the c j-column of diagram B Ž l.. Then e kq2, kq1 s 1 and e kq2, k s 1. We also have e kq2, i s 1 for i s 1, 2, . . . , k y 1. ŽOtherwise, we choose i as large as possible such that 1 F i F k y 1 and e kq 2, i s 0. By comparing rows for c kq2 , c kq1 , and c k in diagram B Ž l., we have e k, i s e kq1, i s 0, and hence c iq1 ) c i q 1, a contradiction.. Therefore, c i G k q 2 y i for i s 1, 2, . . . , k q 2, and hence condition Ž1. holds. FIG. 7. Conditions for Theorem 3.8. Among the ?Ž k q 3.r2@ entries marked by an asterisk, at most two are zeroes. 218 GRIGGS AND HO We also have e2 k, i s 1 for i s k q 1, k q 2, . . . , 2 k y 1. ŽOtherwise, we choose i as large as possible such that k q 3 F i F 2 k y 2 and e2 k, i s 0. Then e2 k, iq1 s 1. We note that e2 kq1, kq1 s 1 and e2 kq2, kq1 s 0, since c kq 1 s k. By comparing rows for c 2 k , c2 kq1 , and c 2 kq2 in diagram B Ž l., we have e2 kq2, iq1 s e2 kq1, iq1 s 1, and hence c iq1 ) c i q 1, a contradiction.. Therefore, e2 k, i s 0 for i s 1, 2, . . . , k, and condition Ž2. holds. Since e2 k, kq3 s 1, by comparing rows for c 2 k , c 2 kq1 , c 2 kq2 , and c 2 kq3 in diagram B Ž l., we have e2 kq3, kq3 s e2 kq2, kq3 s e2 kq1, kq3 s 1, and hence 2 Ž . c kq 3 G k. So we have Ý kq js1 e kq3, j G k, and hence condition 3 holds. We have checked by computer that the converse of this theorem is true for k s 4, 5, 6, 7. ŽIn particular, the converse with condition Ž3. removed is also true for k s 4, 5, 6.. When k s 8, there are 1276 partitions satisfying all three conditions in Theorem 3.8, but 9 partitions among them have d B Ž l. s 20 / k 2 y k. So the three conditions given in Theorem 3.8 are necessary, but not sufficient, for the associated array of extremal partitions. 4. EVALUATING BOUNDS ON D B Ž n. FOR NONTRIANGULAR NUMBERS n For any nontriangular n, we can write n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, where 1 F r - k. In this section we first prove D B Ž n. F k 2 y k based on Theorem 3.7 and a comparison theorem from w1x. Then we improve this bound to k 2 y 2 k y 1 for k G 4. We also present a lower bound that is likely the actual value. Let L s D`is1 L i , where L i denotes the set containing all partitions of i. For l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . . and m s Ž m 1 , m 2 , . . . . in L, we define a partial ordering Ži.e., a reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive relation. by l F m m li F mi for i s 1, 2, . . . . Then we have the following theorem due to Akin and Davis: THEOREM 4.1 w1, Thm. 3Žc.x. BŽ m .. If l, m g L and l F m , then BŽ l. F Proof. Let x 1 , x 2 , . . . and y 1 , y 2 , . . . Žnot necessarily in nonincreasing order. be the parts of two partitions x and y, respectively. We observe that if x i F yi for i G 1, then x F y. ŽTo verify this, we may assume further, without loss of generality, that the x i ’s are already in nonincreasing order. If y 1 - y 2 , we interchange y 1 and y 2 ; then x i F yi for i G 1 still holds. If y 2 - y 3 , we interchange y 2 and y 3 ; then x i F yi for i G 1 still holds. Continuing this process, eventually we can arrange all yi ’s in nonincreasing order and x i F yi for i G 1 still holds. Therefore x F y.. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 219 Now we assume l, m g L and l F m. Let l s Ž l1 , l 2 , . . . . and m s Ž m 1 , m 2 , . . . ., where l1 G ??? G l s ) l sq1 s 0, m 1 G ??? G m t ) m tq1 s 0, and l i F m i for i G 1. Then the parts of BŽ l. are x 1 s s, x 2 s l1 y 1, x 3 s l2 y 1, . . . , x sq1 s l s y 1, x sq2 s 0, x sq3 s 0, . . . . Similarly, the parts of BŽ m . are y 1 s t, y 2 s m 1 y 1, y 3 s m 2 y 1, . . . , ytq1 s m t y 1, ytq2 s 0, ytq3 s 0, . . . . Since x i F yi for i G 1, we have BŽ l. F BŽ m . by the observation above. Combining this theorem with Theorem 3.7, we can show THEOREM 4.2 w5, 8x. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r - k. Then D B Ž n . F k 2 y k. Proof. Let l & n. It suffices to show d B Ž l. F k 2 y k. We choose m , n such that m & Ž1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1.., n & Ž1 q 2 q ??? qk ., and m F l 2 2 F n . By Theorem 4.1, we have that B Ž k yk . Ž m . F B Ž k yk . Ž l. F Ž k 2yk . Ž . Ž k 2yk . Ž . B n . Note that Theorem 3.7 gives B m s Ž k y 1, k y 2 2 2, . . . , 2, 1. and B Ž k yk . Ž n . s Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 2, 1.. Thus B Ž k yk . Ž l. has the form stated in Theorem 2.1 and d B Ž l. F k 2 y k. We prove an analogue of Lemma 3.3 for nontriangular n. Applying it along with Lemmas 3.4, 3.5, and 3.6 leads to an improved upper bound on D B Ž n. for nontriangular n. LEMMA 4.3. Let l & n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk q r, 1 F r - k, and seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. Ž1. If Ž c t , . . . , c tqky1 . s Ž c tqk , . . . , c tq2 ky1 . s ??? , i.e., c tqi s c tqiqk for i G 0, then d B Ž l. F t y 1. ŽThus we can find d B Ž l. by choosing such t as small as possible.. Ž2 . If c t s k y 1, c tq 1 s k, c tq i s c tq iq k for i G 0, and Ž c tyk , . . . , c ty1 . / Ž c t , . . . , c tqky1 ., then at least one of Ži., Žii. of Lemma 3.3 holds. Proof. Ž1. If c tqi s c tqiqk for i G 0, then each c tqi is the number of parts for some B-cyclic partition, and hence Theorem 2.1 gives k y 1 F c tqi F k for i G 0. In particular, we note that the rows for c t , c tq1 , . . . , c tqky1 in diagram B Ž l. each consists of k y 1 or k ones. Then B Ž ty1. Ž l. has the stated form of Theorem 2.1, since it is represented by the rectangle below c ty1 , after reordering the columns if necessary. Therefore, B Ž ty1. Ž l. is B-cyclic, and hence d B Ž l. F t y 1. Ž2. The proof is similar to that of Lemma 3.3Ž2.. In the last case, we suppose for contradiction that c tyk s k y 1, c tykq1 s k, and k y 1 F c j F k, for j s t y k q 2, t y k q 3, . . . , t y 1. Similar to the proof of Ž1., 220 GRIGGS AND HO then the rectangle below c tyky1 in diagram B Ž l. gives that B Ž tyky1. Ž l. is B-cyclic. Thus, by Theorem 2.1, B Ž tyky1qi. Ž l. s B Ž ty1qi. Ž l. for i G 0. Counting the number of parts in each partition, we have Ž c tyk , . . . , c ty1 . s Ž c t , . . . , c tqky1 ., a contradiction. THEOREM 4.4. Let n be nontriangular, n s 1 q 2 q ??? q Ž k y 1 . q r , 1 F r - k. Then Ž1. Ž2. D B Ž n. F k 2 y 2 k y 1 for k G 4; furthermore, equality holds when k G 4 and r s k y 1. Proof. Ž1. We may assume k G 5, since we have D B Ž n. F 7 for k s 4 from Fig. 1. Let l & n. It suffices to show d B Ž l. F k 2 y 2 k y 1. Let seq B Ž l. s ² c1 , c 2 , . . . :. Let B Ž ty1. Ž l. be B-cyclic for some t G 1. Then Theorem 2.1 gives c tqi s c tqiqk and k y 1 F c tqi F k for i G 0. Further, we may assume c t s k y 1 and c tq1 s k, since r / k. We choose such t as small as possible. If t F k, then d B Ž l. F t y 1 F k y 1 - k 2 y 2 k y 1, since k G 5. So we may assume t G k q 1 and Ž c tyk , . . . , c ty1 . / Ž c t , . . . , c tqky1 .. Then, by Lemma 4.3, at least one of Ži., Žii. of Lemma 3.3 holds. If Žii. holds with q s p q k, we have Ž p, q . s Ž t y k q 1, t q 1.. Note that Lemma 3.4 gives p q k F n q 1. Then d B Ž l. F t y 1 s p q k y 2 F n y 1 - k 2 y 2 k y 1, since k G 5. Else, if Ži. or Žii. holds and q F p q k y 2, by Lemmas 3.5 and 3.6, seq B Ž l. has at most k 2 y 3k y 1 terms before the c p-term. Then d B Ž l. F t y 1 F Ž p y 1. q k F Ž k 2 y 3k y 1. q k s k 2 y 2 k y 1. Else, suppose for contradiction that Ži. or Žii. holds with q s p q k y 1: if Ži. holds with q s p q k y 1, we have Ž p, q . s Ž t y k, t y 1. and c ty1 s k q 1, which is a contradiction, since, by Proposition 3.2Ž2., we have c ty1 F k; else, Žii. holds with q s p q k y 1, we have Ž p, q . s Ž t y k q 2, t q 1. and c tykq2 s k y 2, which is also a contradiction, since, by comparing rows for c tq1 and c t in diagram B Ž l., we have c tykq2 / k y 2. Ž2. Assume k G 4 and r s k y 1. By Ž1., it suffices to present l & n such that d B Ž l. s k 2 y 2 k y 1. Let l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l kq1 ., where l1 s k y 1, l2 s k y 2, l i s k y i q 1 for i s 3, 4, . . . , k, and l kq1 s 1. Imitating the proof of Theorem 3.1, we can show that d B Ž l. s k 2 y 2 k y 1. So far we have obtained an upper bound for D B Ž n. in Theorem 4.4. Next we will find a lower bound for D B Ž n. and conjecture this lower bound is the actual value of D B Ž n.. 221 CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS LOWER BOUND THEOREM 4.5. 1 F r F k, For n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, G 3, ¡Ž k y 3 y r . k q r q 2, for 1 F r - ~ for r s D B Ž n . G n y k q 1, ¢Ž r y 2. k q r , for ky1 2 ky1 2 kq1 2 or , kq1 2 , - r F k. Proof. It suffices to present l & n such that d B Ž l. is the stated lower bound on D B Ž n.. We consider three cases Žassociated arrays for extremal partitions in Cases Ž1. and Ž3. are illustrated in Fig. 8.: Case Ž1.. 1 F r - ?Ž k y 1.r2@. Let l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l k ., where l1 s k y 2, l i s k y i for i s 2, 3, . . . , k y r y 1, and l i s k y i q 1 for i s k y r, k y r q 1, . . . , k. Imitating the proof of Theorem 3.1, we can show that d B Ž l. s Ž k y 3 y r . k q r q 2. Case Ž2.. r s ?Ž k y 1.r2@ or ?Ž k q 1.r2@. Let l s Ž1, 1, . . . , 1. with n parts of 1. By applying induction on i, we can show that B Ž1q1q2q3q? ? ?qi. Ž l. s Ž n y Ž1 q 2 q ??? qi ., i, i y 1, i y 2, . . . , 2, 1. for i s 1, 2, . . . , k y 2. Thus d B Ž l. s 1 q 1 q 2 q 3 q ??? qŽ k y 2. q Ž r y 1. s n y k q 1. FIG. 8. Associated arrays for two extremal partitions in Theorem 4.5. 222 GRIGGS AND HO Case Ž3.. ?Ž k q 1.r2@ - r F k. Let l s Ž l1 , l 2 , . . . , l kq1 ., where l i s k y i for i s 1, 2, . . . , k y r q 1, l i s k y i q 1 for i s k y r q 2, k y r q 3, . . . , k, and l kq 1 s 1. Imitating the proof of Theorem 3.1, we can show that d B Ž l. s Ž r y 2. k q r. CONJECTURE 4.6 w5x. Ž1. Assume n G 3. If n g 1 q 2 q ??? q Ž K y 1 . , 1 q 2 q ??? q Ž K y 1 . q Ky2 2 , then D B Ž n. strictly decreases from Ž K y 1. 2 y Ž K y 1. to uŽ K 2 y 2 K .r2v. Ž2. If n g 1 q 2 q ??? q Ž K y 1 . q Ky2 2 , 1 q 2 q ??? q Ž K y 1 . q K , then D B Ž n. strictly increases from uŽ K 2 y 2 K .r2v to K 2 y K. Actually Etienne gave K 2 y K instead of Ž K y 1. 2 y Ž K y 1. in Ž1. and gave Ž K q 1. 2 y Ž K q 1. instead of K 2 y K in Ž2.. Both of these seem to be mistakes. According to w5x, this conjecture was confirmed for n s 3, 4, 5, . . . , 55. Here we suggest a stronger conjecture that is confirmed for n s 3, 4, 5, . . . , 36 Žsee Fig. 1., and also for r s k y 1, k. CONJECTURE 4.7. ‘‘D B Ž n. s .’’ In Theorem 4.5 ‘‘D B Ž n. G ’’ can be replaced with 5. CAROLINA SOLITAIRE: A VARIATION OF BULGARIAN SOLITAIRE Let us now define Carolina Solitaire formally, and then derive analogues of some of the results for Bulgarian Solitaire. For a positive integer n, we say l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . . is a composition of n, and we write l * n, provided that the positive integers l1 , l2 , . . . , l s Žnot necessarily in nonincreasing order. add up to n and l i s 0 for i G s q 1. We say such l has s Žpositive. parts, and we often drop the zeroes, writing l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s .. The shift operation C on l is the composition of n, denoted C Ž l., obtained by decreasing each part l i by one, inserting a part s s as the first part, and discarding any zero parts. So C Ž i. Ž l. denotes the composition obtained by successively applying the shift operation C to l a total of i times. Starting with a composition l, we describe Carolina Solitaire by CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 223 repeatedly applying the shift operation C to obtain the sequence of compositions l , C Ž l . , C Ž2. Ž l . , . . . . For a couple of simple examples, we note that l s Ž2, 1, 1, 1, 1. * 6 gives the sequence Ž2, 1, 1, 1, 1., Ž5, 1., Ž2, 4., Ž2, 1, 3., Ž3, 1, 2., Ž3, 2, 1., Ž3, 2, 1., . . . , while l s Ž6, 1. * 7 yields Ž6, 1., Ž2, 5., Ž2, 1, 4., Ž3, 1, 3., Ž3, 2, 2., Ž3, 2, 1, 1., Ž4, 2, 1., Ž3, 3, 1., Ž3, 2, 2., Ž3, 2, 1, 1., Ž4, 2, 1., . . . . The first example is fixed at the composition Ž3, 2, 1. after five steps, while the second example reaches a cycle after four steps. We say a composition m s Ž m 1 , m 2 , . . . , m s . * n is a permutation of a composition l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . * n if the parts m i of m are a permutation of the parts l i of l. We notice the connection between Bulgarian Solitaire and Carolina Solitaire: If m * n is a permutation of l & n then, for i ) 0, C Ž i. Ž m . * n is a permutation of B Ž i. Ž l. & n. Similar to B-cyclic partition, d B Ž l., and D B Ž n. in Bulgarian Solitaire, we can define Žresp.. C-cyclic composition, d C Ž l., and D C Ž n. in Carolina Solitaire: We say a composition m * n is C-cyclic if C Ž i. Ž m . s m for some i ) 0. We will prove in Theorem 5.1 that l * n is C-cyclic if and only if l & n is B-cyclic. To measure how long it takes for Carolina Solitaire to cycle, for l * n we let d C Ž l. denote the smallest integer i G 0 such that C Ž i. Ž l. is C-cyclic. Let D C Ž n. [ max d C Ž l.: l * n4 , so that for any l * n, D C Ž n. steps reach a cycle. Trivially, D C Ž1. s D C Ž2. s 0 and D C Ž3. s 3. The values of D C Ž n., 4 F n F 36, are displayed in Fig. 9, which we worked out by computer. The data are arranged using the representation n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r F k. We will show in Theorem 5.5 that D C Ž n. s k 2 y 1 whenever n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk. When n is a nontriangular number, we will prove in Theorem 5.8 that D C Ž n. F k 2 y k y 2 for k G 4. We also present in Theorem 5.9 a lower bound for D C Ž n. that we conjecture is the correct value in general. FIG. 9. D C Ž n. for n s 4, 5, . . . , 36. 224 GRIGGS AND HO Now we start with the characterization of C-cyclic compositions. Similarly to the associated Ž0, 1.-array for a partition, we can define the associated Ž0, 1.-array for a composition l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . * n: ` Ml s w m i j x i , js1 , where m i j s ½ 1, if j F s and i F l j , 0, otherwise. The columns of Ml correspond to the parts of l. We notice that MC Ž l. can be obtained directly from Ml by a shifting process on a Ž0, 1.-array: Assume l s Ž l1 , l2 , . . . , l s . * n and its associated array Ml is given. Step 1: Diagonally circular shifting. This is the same as Step 1 for Bulgarian Solitaire described in Section 2. After Step 1, we obtain a new array; denote it MlX . Note that the numbers of ones in columns of MlX are s, l1 y 1, l 2 y 1, . . . , l s y 1, 0, 0, 0, . . . . If l i y 1 s 0 and l iq1 y 1 ) 0 for some i, then we need an extra step to obtain MC Ž l. . Otherwise, MlX is the array MC Ž l . . Step 2: Left shifting. Whenever there is some integer j such that the jth column of MlX is an all-zero column and the Ž j q 1.th column of MlX is not an all-zero column, we remove the jth column and shift each column with larger index one column to the left. We repeat this shifting until there does not exist such an integer j. Using the shifting process described above and imitating the proof of Theorem 2.1, we can show THEOREM 5.1. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r F k. Then l * n is C-cyclic if and only if l has the form Ž k y 1 q d ky 1 , k y 2 q d ky2 , . . . , 2 q d 2 , 1 q d 1 , d 0 . , 1 where each d i is 0 or 1 and Ý ky is0 d i s r. COROLLARY 5.2. If n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, then Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 2, 1. is the unique C-cyclic composition of n. By Theorems 2.1 and 5.1, l * n is C-cyclic if and only if l & n is B-cyclic. So the number of cycles for Carolina Solitaire is the same as that for Bulgarian Solitaire. Next we shall prove D C Ž n. s k 2 y 1 for triangular n. PROPOSITION 5.3. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk and l * n. Then l is a permutation of Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 2, 1. if and only if d C Ž l. F k y 1. CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS 225 Proof. If l is a permutation of Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 1., it is easy to see that C Ž ky1. Ž l. s Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 1. and d C Ž l. F k y 1. If l is not a permutation of Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 1., then there exists m s C Ž i. Ž l., i G 0, such that m is not a permutation of Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 1. and C Ž m . is a permutation of Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 1.. We note that m must be a permutation of Ž k q 1, k y 1, k y 2, k y 3, . . . , 2., and hence C Ž ky1. Ž m . s Ž k, k y 1, . . . , 3, 1, 2. is not C-cyclic. Therefore, d C Ž m . G k and d C Ž l. G k. Combining Proposition 5.3 with Theorem 2.1, we have the following corollary that describes the relation between Carolina Solitaire and Bulgarian Solitaire when n is a triangular number. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk and let l * n be a permuta- COROLLARY 5.4. tion of l9 & n. Ž1. Ž2. d C Ž l. F k y 1 if and only if d B Ž l9. s 0. If d C Ž l. G k then d C Ž l. y d B Ž l9. s k y 1. Combining Corollary 5.4 with Theorem 3.7, we can prove: THEOREM 5.5. If n s 1 q 2 q ??? qk, then D C Ž n . s k 2 y 1. Now we turn our attention to the value of D C Ž n. for nontriangular n. PROPOSITION 5.6. Let l * n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r - k. Ž1. If l is a permutation of some C-cyclic composition of n, then Ž d C l. F k y 1. Ž2. If l is not a permutation of any C-cyclic composition of n, then d C Ž l. G k y 1. Proof. Ž1. Assume l is a permutation of m * n, where m has the stated form of Theorem 2.1. Then we note that C Ž ky1. Ž l. also has the stated form of Theorem 2.1. Thus C Ž ky1. Ž l. is C-cyclic and d C Ž l. F k y 1. Ž2. It is easy to verify the statement for k F 3. So we may assume k G 4. If l is not a permutation of any C-cyclic composition of n, then there exists m s C Ž i. Ž l., i G 0, such that m is not a permutation of any C-cyclic composition and C Ž m . is a permutation of some C-cyclic composition. By Theorem 2.1, we note that m must be a permutation of Ž k q d ky 1 , k y 2 q d ky3 , k y 3 q d ky4 , . . . , 3 q d 2 , 2 q d 1 , d 0 q d ky2 ., where each d i is 0 or 1, d 0 F d ky2 , and Ž d ky1 , d ky2 . / Ž0, 1.. Then C Ž ky2. Ž m . does not have the stated form of Theorem 2.1. So d C Ž m . G k y 1, and hence d C Ž l. G k y 1. 226 GRIGGS AND HO We note that from the condition ‘‘d C Ž l. s k y 1’’ we cannot determine whether l is a permutation of some C-cyclic composition of n. For example, when k s 4, l s Ž3, 2, 4. * 9 with d C Ž l. s 3 is a permutation of the C-cyclic composition Ž4, 3, 2.; however, l s Ž5, 4. * 9 with d C Ž l. s 3 is not a permutation of any C-cyclic composition. Similarly to Corollary 5.4 for triangular n, we have the following corollary that describes the relation between Carolina Solitaire and Bulgarian Solitaire when n is not a triangular number: COROLLARY 5.7. Let n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, 1 F r - k, and let l * n be a permutation of l9 & n. Ž1. If d C Ž l. F k y 2 then d B Ž l9. s 0. Ž2. If d C Ž l. G k y 1 then d C Ž l. y d B Ž l9. s k y 2 or k y 1. Proof. Ž1. follows immediately from Proposition 5.6Ž2. and we can prove Ž2. by applying induction on d C Ž l.. ŽFor the induction basis, we note that if d C Ž l. s k y 1, then d B Ž l9. s 0 or 1 by Proposition 5.6.. We are now in a position to prove THEOREM 5.8. 1 F r - k. Then Let n be nontriangular, n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r, Ž1. D C Ž n. F k 2 y k y 2 for k G 4; Ž2. furthermore, equality holds when k G 4 and r s k y 1. Proof. Ž1. follows from Theorem 4.4 and Proposition 5.7. To prove Ž2., it suffices to present l * n such that d C Ž l. s k 2 y k y 2. Let l s Ž l1 , l 2 , . . . , l kq1 ., where l1 s k y 1, l2 s k y 2, l i s k y i q 1, for i s 3, 4, . . . , k, and l kq 1 s 1. Imitating the proof of Theorem 3.1, we can show that d C Ž l. s k 2 y k y 2. Using the results for D B Ž n. and considering the relations between d C Ž l. and d B Ž l., we have proven Theorems 5.5 and 5.8 for D C Ž n.. We can also prove these two theorems in another way: Note that we have Lemmas 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.6, and 4.3 for Bulgarian Solitaire. If we consider analogous lemmas for Carolina Solitaire, then we can prove Theorems 5.5 and 5.8 directly. Similarly to Theorem 4.5 for D B Ž n., we have the following ‘‘lower bound theorem’’ for D C Ž n.: 227 CYCLING UNDER REPEATED SHIFTS LOWER BOUND THEOREM 5.9. 1 F r F k, ¡Ž k y 2 y r . k q r , DC Ž n . G~ For n s 1 q 2 q ??? qŽ k y 1. q r G 3, for 1 F r - n y 1, for n, for ¢Ž r y 1. k q r y 1, for ky1 2 ky1 2 kq1 2 ky1 2 FrF FrF , kq1 2 kq1 2 and r s 1, and r G 2, - r F k. Proof. Similarly to the proof of Theorem 4.5, we consider three cases: 1 F r - ?Ž k y 1.r2@, ?Ž k y 1.r2@ F r F ?Ž k q 1.r2@, and ?Ž k q 1.r2@ - r F k. For each case, we take the same extremal partition Žcomposition. as that in the proof of Theorem 4.5. We conclude this paper by giving the following conjecture that is confirmed for n s 3, 4, . . . , 36 Žsee Fig. 9., and also for r s k y 1, k. CONJECTURE 5.10. ‘‘D C Ž n. s .’’ In Theorem 5.9 ‘‘D C Ž n. G ’’ can be replaced with ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to Andrey Andreev for introducing us to Bulgarian Solitaire and Carolina Solitaire. We thank Ron Graham for pointing us to the literature on Bulgarian Solitaire. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. E. Akin and M. Davis, Bulgarian solitaire, Amer. Math. Monthly 4 Ž1985., 237]250. H.-J. Bentz, Proof of the Bulgarian Solitaire conjectures, Ars Combin. 23 Ž1987., 151]170. J. Brandt, Cycles of partitions, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 85 Ž1982., 483]486. C. Cannings and J. Haigh, Montreal solitaire, J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 60 Ž1992., 50]66. G. Etienne, Tableaux de Young et solitaire bulgare, J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 58 Ž1991., 181]197. M. Gardner, Mathematical games, Scientific American 249 Ž1983., 12]21. J. D. Hobby and D. Knuth, Problem 1: Bulgarian Solitaire, in ‘‘A Programming and Problem-Solving Seminar,’’ Department of Computer Science, Stanford University, Stanford ŽDecember 1983., pp. 6]13. K. Igusa, Solution of the Bulgarian solitaire conjecture, Math. Mag. 58 Ž1985., 259]271. R. Servedio and Y. N. Yeh, A bijective proof on circular compositions, Bull. Inst. Math. Acad. Sinica 23 Ž1995., 283]293. Y. N. Yeh, A remarkable endofunction involving compositions, Stud. Appl. Math. Ž1995., 419]432.