KABLE A STUDY IN FEDERALISM AND RIGHTS PROTECTION

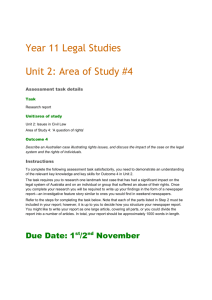

advertisement