BUILDING BRIDGES IN AUSTRALIAN CRIMINAL LAW: CODIFICATION AND THE COMMON LAW

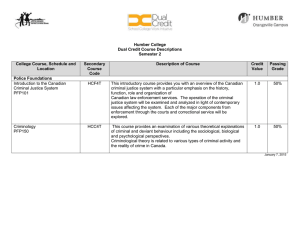

advertisement