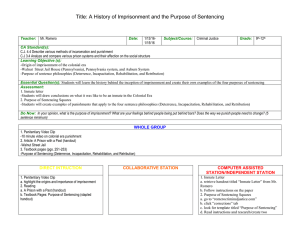

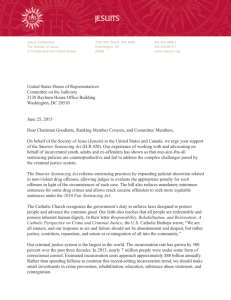

ADDRESSING THE CURIOUS BLACKSPOT THAT IS LEGALITY AND SENTENCING

advertisement