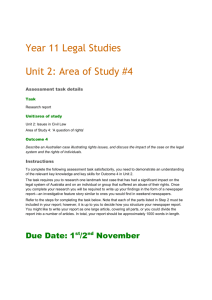

THE PRINCIPLE OF LEGALITY: ISSUES OF RATIONALE AND APPLICATION

advertisement