SENTENCES WITHOUT CONVICTION: PROTECTING AN OFFENDER FROM UNWARRANTED DISCRIMINATION IN EMPLOYMENT

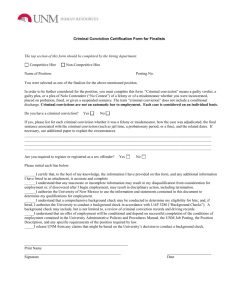

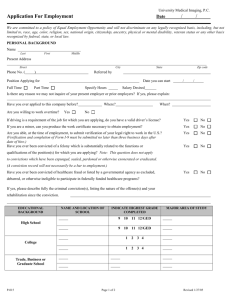

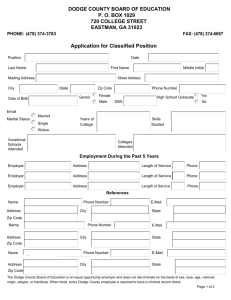

advertisement