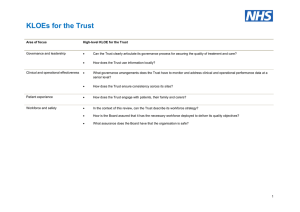

Governance of New Global Partnerships Challenges, Weaknesses, and Lessons

advertisement