Document 11238227

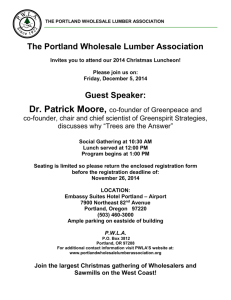

advertisement