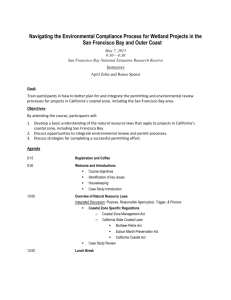

VI. The Association of Bay ... Governments (ABAG) Region

advertisement