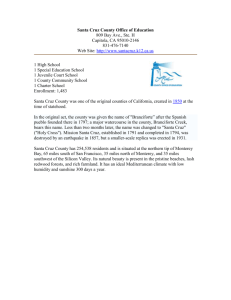

IV. The Central Coast Region

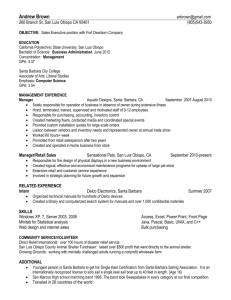

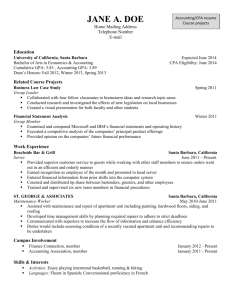

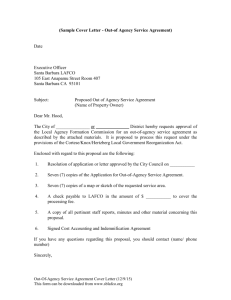

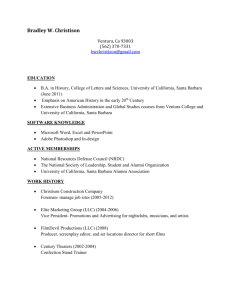

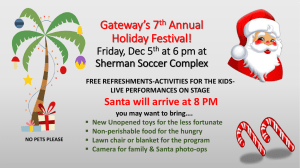

advertisement