Perspectives of the Forest Products Industry on Management Strategies 1

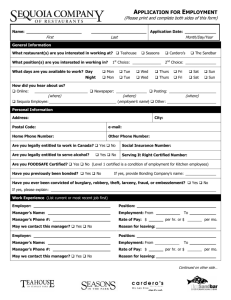

advertisement

Perspectives of the Forest Products Industry on Management Strategies1 Glen H. Duysen2 Abstract: Past history indicates a wide range of management strategies in the giant sequoia groves of Tulare and Fresno counties. The variation in management is a result of grove ownership, Federal and state regulations and policies, and public sentiment. When the West was developing in the late 1800's, lumber from the giant sequoia was a highly desired product. Private groves were harvested. These lands now are stocked with second-growth sequoia, pine, fir, and cedar. Management activities since the 1930's on Forest Service, state, Native American, and private properties have been confined to the removal of the white wood species. Management of sequoia groves on Federal park lands has been limited to control burning for fire protection. Regardless of the management strategy applied during the past 120 years, the giant sequoia specimen tree is a most hearty "soul," maintaining a defiant stance against old age, fire, wind, drought, and man's activities. Current management strategies on Federal lands are mandated by law, regulation, or management plans, and basically provide only for fire protection for the sequoia groves. Selective harvesting of white wood species in sequoia groves on state land has resulted in healthy, esthetically pleasing, timber stands, which the forest products industry strongly supports. Management strategies for all ownerships should provide for the reproduction of the giant sequoia species. As a fast growing tree adaptable to the local climate, the establishment of giant sequoia reproduction for future national lumber requirements on state, private, and Forest Service lands is a worthy goal. My comments today are based on my observations as a licensed professional forester, working in and around both public and private giant sequoia groves for the past 25 years in Tulare and Fresno counties. We can learn much about the giant sequoia species by examining three different management strategies practiced over the past 120 years. As California developed in the 1880's, the first strategy involved the demand for redwood lumber. Many small sawmills were constructed on private property. A major species milled was specimen size giant sequoias. Evidence of this practice can be found in the Converse Basin, Dillonwood, and Mountain Home. Although generally regarded as a poor management practice today, these lands currently support a well-stocked stand of second-growth sequoias, with a mixture of the other native conifer species. Since the 1930's, the harvesting of specimen size giant sequoias has been very minor, but logging of the white wood species (pine, fir, and cedar) has occurred within sequoia groves on both Federal, state, and private lands. This management strategy varies from a very light selective harvest to removing all white wood trees. A wide range of other practices have been found within and around the Sequoia 1 An abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the Symposium on Giant Sequoias: Their Place in Ecosystem and Society, June 23-25, 1992, Visalia, California. 2 Resource Manager, Sierra Forest Products, Terra Bella, CA 93270. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-151. 1994. National Forest. On Tule River Native-American land and within their groves, there has been harvesting of the conifer species. The Sequoia Crest grove is an example of summer home development within a grove, which required the removal of the white woods and some second-growth sequoias. Mountain Home State Demonstration Forest has selectively harvested within their groves, resulting in an excellent stand of second-growth sequoia intermixed with pine, fir, and cedar. However, because of Federal laws and regulations, sequoia groves within the USDI National Park boundaries have had limited physical activity. Road construction has been minor, and fire protection management and regeneration has been conducted through control burns. So then what have we learned from these management strategies? There are widely divergent opinions concerning how the entire stand structure should be managed in a grove, but the forest products industry strongly supports the protecttion and preservation of specimen giant sequoia trees. Fire Management and Regeneration Strategies Exposed mineral soil and sunlight are requirements for the regeneration of the species. These two conditions do not occur in the nondisturbed grove. In order to perpetuate the species, we believe manipulation of the surrounding vegetation is essential to attaining the proper seed bed. We do know that although some people believe the giant sequoia tree is a fragile, near-extinct species, there are sufficient examples which indicate the hearty nature of the tree. Major fires over the past 1,000 years have not been able to destroy these magnificent giants. Winter storms, while eliminating an occasional tree, have not caused major damage to the groves. Recent studies have found the giant sequoia to be a very windfirm species throughout the world. Human activities, whether through road construction, logging, or land development, apparently have not affected the longevity and health of the species. Ground disturbances have not occurred for 120 years at the Converse Basin and at Dillonwood, with later activity on the Tule River Native- American Reservation, Camp Lena, and Sequoia Crest. The remaining specimen trees in these groves appear to have remained thrifty and windfirm when compared to groves that have not been entered. The forest products industry emphatically believes our giant sequoia groves should be managed carefully and skillfully, but not treated as an endangered species. Giant sequoia groves do not need or require wide buffer strips or entire drainages set aside as protection measures. 137 Protection from wildfires has been a high priority for many years in the management of giant sequoia groves on both National Park Service and USDA Forest Service lands. This protection has created problems and becomes more difficult over the years because of the elimination of periodic ground fires, and the rapid growth of understory stands of the conifer species. To reduce the fire hazard to the groves in recent years, two methods have been used: controlled ground fires and mechanical removal. The National Park Service has taken the lead in the use of controlled ground fire to reduce the catastrophic wildfire potential. The forest products industry, while realizing the limitations under which the Park Service operates due to laws and regulations, has the following general concerns in the use of control burning: • Difficult to control intensity of burn; • Creates additional air pollution; • End product is not esthetically pleasing; • Site preparation is often not adequate for regeneration; • Destroyed conifer resource not utilized. The Forest Service has advocated mechanical methods to remove the fire potential in their groves and to promote regeneration. With the signing of the Mediated Agreement for the Sequoia National Forest in 1990, mechanical entry into the Sequoia groves is not permitted except for the specific purpose of reducing the fuel loads, after analysis through a grove Environment Impact Statement. Mechanical entry has several advantages: •Method can be controlled; •Removed white woods can be utilized; •Sites quickly heal esthetically; •An adequate seed bed can be prepared; •Visibility of specimen trees can be enhanced. A Multiple-Use Strategy Another land management practice worthy of discussion can be found on the Mountain Home State Demonstration Forest (this strategy was also used on selected areas of the Sequoia National Forest). Selective and small group harvesting of white wood species within giant sequoia groves in the State Forest has been the practice for many years. A multi-age stand of healthy pine, fir, and cedar co-exist with the specimen size giant sequoias. The timber stand has been 138 opened sufficiently to permit the establishment of secondgrowth sequoias. Specimen trees are visible to the visiting public. Recreation is the first priority in the management of the State Forest, and the numerous campgrounds are heavily used. This is living proof that timber management, even in giant sequoia groves, can be in harmony with recreation and wildlife. The forest products industry strongly supports the multiple-use concept as exemplified on Mountain Home State Demonstration Forest. Their managers over the years are to be praised for their progressive and dedicated approach to managing this natural resource. Diverse ownership and management strategies are supported by the forest products industry. We are aware that on Federal lands the strategies are often dictated by law, regulation, and mediated management plans. State, NativeAmerican, and private lands are managed under different circumstance. We also recognized the reasons for the differences. We do not advocate the same strategy for all ownerships. We strongly reject the view that a single management strategy for all giant sequoia groves, whether National Park, National Forest, state or private, is in the best long-term interest of the groves or the American people. We also reject the non-management concept. Non-management is bad management. The development of second-growth commercial stands of giant sequoia on USDA Forest Service, state, and private land should also be pursued. As a fast growing and desirable commercial species, second-growth giant sequoias may help to supply the need for wood products for our future generations. Conclusion This symposium has presented different views on Sequoia grove management; presenting these different strategies is a constructive problem-solving method. Only through open dialog and the sharing of information will we be able to do the best job in managing our respective natural resources. The use of misinformation and broad accusations in order to influence the public has no place in sound resource management. It is evident from the quality of speakers that the giant sequoia is in no danger of extinction or is being mismanaged in any ownership. All participants at this symposium have the responsibility to speak honestly and professionally with the public and our elected representatives. If we do not tell the whole story, then we should not consider ourselves professionals. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-151. 1994